A Study of the Effectiveness of the Composite Burn Index (CBI) in Assessing the Severity of Forest Soil Fires in Latakia Governorate

The connection of scientific research with the requirements of development in a society in all fields is one of the basic foundations for social advancement. Research and development (R&D) require a strong linkage between scientific research bodies (SRBs) and the society represented by productive and service bodies (PSBs) in order to allow these bodies to identify their needs and develop their research plans accordingly. Thus, we could reach translational scientific research that constitutes a foundation clearly linked to development goals.

The terrorism that afflicted the country and the destruction that befell many development sectors, the most important of which is the industrial sector, has led to the exit of a group of production lines and machines from service as a result of their destruction or suspension for a long period of time, and especially their old operating software. The option of importing machines and software has become not possible as a result of the forced economic blockade on the country, noting that the import process is the most difficult option, as it is considered a drain on foreign exchange due to the high cost.

It does not achieve self-sufficiency and creates technical dependence on the exporting countries, with negative impact on the production process. The most important solution offered now is to rely on the import substitution policy according to clear and precise criteria that work to define target sectors and materials in line with developmental goals, and defining a local alternative for those materials developed by local academic expertise, aiming to reduce the import bill and thus stopping the depletion of foreign exchange.

On 6/01/2019, the Import Substitution Program (ISP) was approved at the Cabinet meeting, and it was decided to assign the Ministry of Economy and Foreign Trade to follow up on the implementation of the program in coordination with whoever is needed, according to the Prime Minister’s document No. 1/231 dated 1/9/2019.

As the program aims to reduce the import bill for commodities that can be produced locally, stop the depletion of foreign exchange, and achieve self-sufficiency in a number of materials, according to a set of economic considerations related to the efficient use of resources and focus on quality issues. Nevertheless, by reviewing the materials and sectors included in the program, one could note the absence of imports software, despite its significant impact on the industry and the economy in general, and its ability to achieve acceptable economic savings in the event that it is replaced by scientific research outputs.

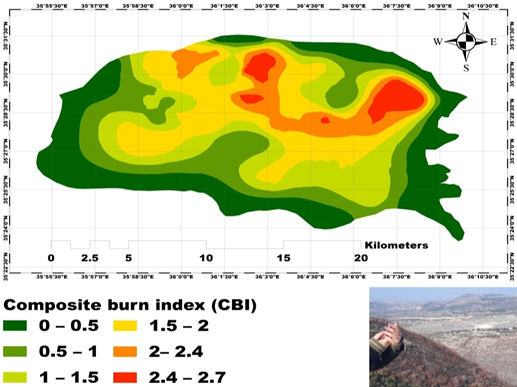

To clarify this statement, a field study was conducted in some companies that took individual initiatives to rehabilitate some of their machines and put them back to service through local scientific research cadres. / 3 / companies were selected; two companies from the public sector, one from the private sector, in addition to meeting with one of the local academic expert to demonstrate the ability of local experiences to secure the authentic alternatives. Through field visits and interviews with the concerned personnel, some information was collected that clarified the reality of substituting software imports, and the possibility of research capabilities and local expertise to contribute to the import substitution program.

By asking the following questions:

The study reached a set of results, the most important is that software imports are not included in the ISP, with many machines and production lines stopped in public and private sector companies for software defects, despite the existence of research capabilities, local expertise and research outputs capable of rehabilitating these machines through providing a software alternative, thus replacing with imported ones, in addition to the possibility of developing these machines, as local expertise could add additional features to them. Nonetheless, this comes with the assurance that the outputs provided by these rehabilitated machines are in accordance with the approved standard specifications and with the required quality. Thus, it ensures the operational and development side and the quality of the output.

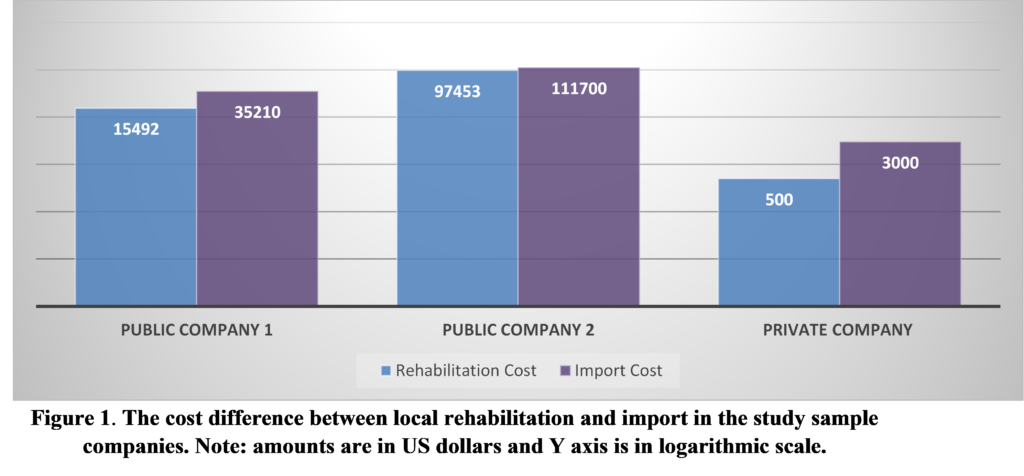

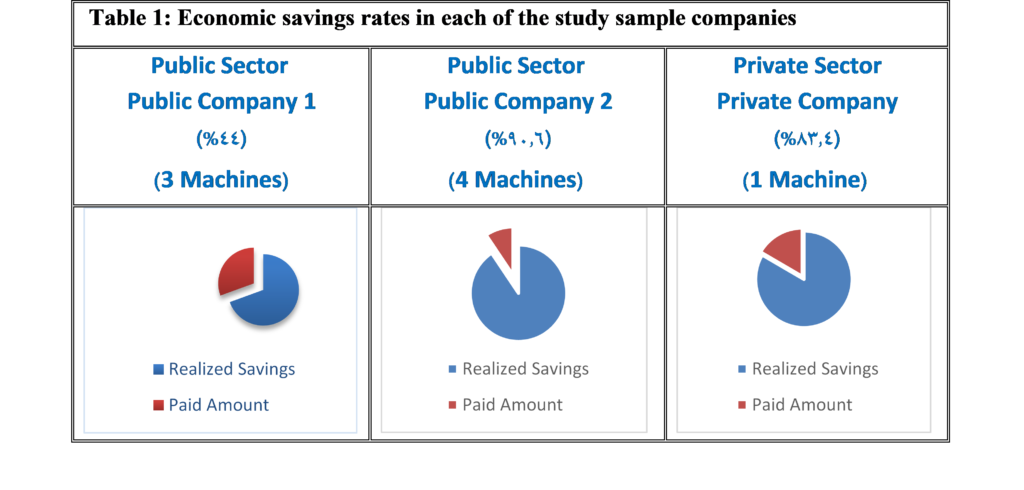

Figure 1 and Table 1 show the cost difference between local rehabilitation and import in the study sample companies, in addition to the economic savings achieved. We found that replacing the appropriate software indeed works to achieve the basic objectives of the program and ensures the relative weight of the software, and these achieved savings are only for some machines selected from very few public and private industrial sector institutions, and therefore we can conclude the extent of the economic savings that will be achieved from including software in the import substitution program and applying this principle at all institutions and companies in the industrial sector.

The study also showed the experience of one of the local experts in converting student projects into applied projects that met the needs of the authorities, meeting their objectives and provide them with the best results. Among 16 research projects, 9 of them were applied, hence this is a very acceptable percentage and reflects the ability of those research experiences to meet the needs of productive entities. In fact, it can be said that the scientific and research authorities in Syria have the ability to support the various development sectors through ISP, working on developing these sectors and achieving meaningful economic savings.

Our results also show that there are many obstacles that prevent the success of the interlinking between the SRBs and PSBs, the most important of which is the lack of institutionalization of the interdependence process among them.

Our results also show that there are many obstacles that prevent the success of the interlinking between the SRBs and PSBs, the most important of which is the lack of institutionalization of the interdependence process among them.

The communication process, as in the current situation, is a routine and ineffective process that depends on personal relationships, and this is ineffective most of the time. Therefore, it is necessary to institutionalize this interlinking and work to create an ecosystem that secures real and effective networking between the two parties according to clear principles and mechanisms. In this regard, technology transfer mechanism must be ongoing from research and development centers to industry, and making the best use of the technology transfer system in the Syrian Arab Republic, which the Higher Commission for Scientific Research (HCSR) has recently established.

In addition, obstacles related to funding and adequate financial support for the completion of research projects are dominating, and hence, it is necessary to increase the funds allocated for scientific research. Finally, we defined obstacles related to the integration of specializations required to complete the project. This constraint can be solved by forming research teams with integrated specializations to ensure the completion of the project with the required accuracy.

In conclusion, it can be said that scientific research and technological development are of great importance during crises, and have a major role in contributing to the re-advancement of the various development sectors, as the importance of scientific research lies in its translational outputs through appropriate investment. Linking SRBs to PSBs and society, and the transfer of applied scientific knowledge/technology are not exclusive to the use of technology or creating a correct business environment, but rather is a matter of knitting multiple relationships between production, transfer and investment of knowledge altogether.

The actual aim is to provide a vision for the future role that scientific research can play in comprehensive development (human – economic – knowledge) in Syria, including the field of imports substitution, especially software imports, and its role in reducing the import bill and improving the competitiveness of the business sectors (both productive and service), and to understand how issues affecting business sectors can be transformed into ideas for translational research and innovation.

Note: This analysis was done during a training joint program between the National Institute of Public Administration (INA) and the higher commission for scientific research (HCSR), and was supervised by both Dr. Ghaith Saker, the scientific deputy manager of HCSR as well as the general director of HCSR, Dr. Majd Aljamali.

Acknowledgments: We do thank Dr. Ayham Assad, the director of research and consulting department at the National Institute of Public Administration (INA) for his supervision during the training period and Dr. Bassel Younis for his generous help.

INTRODUCTION

Despite being broadly examined in the literature, purchasing power parity (PPP) is still at the center of attention due to the lack of consensus on its empirical validity. The relative version of the PPP postulates that changes in the nominal exchange rate between a pair of currencies should be proportional to the relative price levels of the two countries concerned. When PPP holds, the real exchange rate, defined as the nominal exchange rate adjusted for relative national price level differences, is a constant [1].

Tests conducted to validate the PPP have developed pari passu with advances in econometric techniques. A major strand of this literature focused on the stationarity of real exchange rates as stationary implies mean reversion and, hence, PPP. Earlier studies that analyzed the stationarity of real exchange rate are generally based on linear conventional unit root tests, such as the augmented dickey fuller (ADF), the Phillip Perrons (PP) and the Kwiatkowski, Phillips, Schmidt and Shin (KPSS). However, these unit root tests suffer from low power for finite samples. To address this problem, a new trend of studies started applying long-span data sets. Nonetheless, a potential problem with these studies is that the long-span data may be inappropriate because of possible regime shifts and differences in real exchange rate behavior [1,2]. To overcome this potential problem, an innovation was made possible by the appearance of unit root tests that allow for one or multiple structural breaks, such as Perron (1989), Zivot and Andrews (1992), Lumsdaine and Papell (1997) and Lee and Strazicich, (2003, 2004) test [3-7].

Another approach undertaken by the literature to circumvent the problem of low-power is to apply panel unit root techniques in the empirical tests of PPP. One criticism of these tests relates to the fact that rejecting the null hypothesis of a unit root implies that at least one of the series is stationary, but not that all the series are mean reverting [8,9].

The issues raised by the long-span and the panel-data studies explain the first PPP puzzle.

A second related puzzle also exists. It is summarized in Rogoff (1996) as follows: “How can one reconcile the enormous short-term volatility of real exchange rates with the extremely slow rate at which shocks appear to damp out?”[10]. Based on the theoretical models of Dumas and Sercu et al, this second PPP puzzle introduced the idea that the real exchange rate might follow a nonlinear adjustment toward the long-run equilibrium due to transactions costs and trade barriers [11,12].

Recognizing the low power of conventional unit root tests in detecting stationarity of real exchange rates with nonlinear behavior, new testing approaches have emerged, which consider the nonlinear processes explicitly. Among others, Obstfeld and Taylor (1997) [13], Enders and Granger (1998) [14] and Caner and Hansen (2001) [15] suggested to investigate the nonlinear adjustment process in terms of a threshold autoregressive (TAR) model. This model allows for a transactions costs band within which arbitrage is unprofitable as the price differentials are not large enough to cover transaction costs. However, once the deviation from PPP is sufficiently large, arbitrage becomes profitable, and hence the real exchange rate reverts back to equilibrium [13,16]. More specifically, real exchange rate tends to revert back to equilibrium only when it is sufficiently far away from it, which implies that it has a nonlinear adjustment toward the long-run equilibrium [9,17-19].

While transaction costs have most often been advanced as possible contributors to nonlinearity in real exchange rates, it is argued that nonlinearity may also arise from heterogeneity in agents’ opinions in foreign exchange rate markets. As discussed in Taylor and Taylor [20], as nominal exchange rates have extreme values, a greater degree of consensus concerning the appropriate direction of exchange rates prevails, and international traders act accordingly.

Official intervention in the foreign exchange market when the exchange rate is away from equilibrium is another argument for the presence of nonlinearities [20]. According to Bahmani-Oskooee and Gelan, we expect a higher degree of nonlinearity in the official real exchange rates of less developed countries compared to those of developed countries due to a higher level of intervention in the foreign exchange market in the former [21].

In the presence of transaction costs, heterogeneous agents and intervention of monetary authorities, many of authors (e.g., Dumas [11]; Terasvirta, [22]; Taylor et al [17]) suggest that the nonlinear adjustment of real exchange rate is smoother rather than instantaneous. One way to allow for smooth adjustment is to employ a smooth transition autoregressive (STAR) model that assumes the structure of the model changes as a function of a lag of the dependent variable [23].

In this context, Kapetanious et al developed a unit root test that has a specific exponential smooth transition autoregressive (ESTAR) model to examine the null hypothesis of non-stationarity against the alternative of nonlinear stationarity [16]. This model suggests a smooth adjustment towards a long-run attractor around a symmetric threshold band. Hence, small shocks with transitory effects would keep the exchange rate inside the band, while large shocks would

push the exchange rate outside the band. Once this band is exceeded, the series would display mean-reverting behavior. The jump outside the band is supposed to be corrected gradually [16].

More recently, modified versions of the nonlinear unit root test of Kapetanious et al, KSS) were proposed by Kılıç and Kruse [19,24]. Both studies observe that their modified tests are in most situations superior in terms of power to the Dickey-Fuller type test proposed by Kapetanios et al. Sollis proposed another extension of ESTAR model, the asymmetric exponential smooth transition auto-regressive (AESTAR) model, where the speed of adjustment could be different below or above the threshold band [25].

Recently, the effect of non-linearity has become popular in testing the validity of PPP (e.g., [9,17,26-31]). These studies provided stronger evidence in favor of PPP compared to the previous studies using conventional unit root tests.

The attention given to testing PPP in Syria has so far been very limited. Hassanain examined the PPP in 10 Arab countries, including Syria, from 1980 to 1999. Using panel unit root tests, he found evidence in favor of the PPP [32]. El-Ramely tested the validity of PPP in a panel of 12 countries from the Middle East, including Syria, for the period 1969-2002. She found that the evidence in support of PPP is generally weak [33]. Cashin and Mcdermott examined the PPP hypothesis for 90 developed and developing countries, including Syria, for the period 1973-2002 [34]. For this purpose, they utilized real effective exchange rates and applied the median-unbiased estimation techniques that remove the downward bias of least squares. The findings provided evidence in favor of the PPP in the majority of countries. Kula et al tested the validity of PPP for a sample of 13 MENA countries, including Syria. For this purpose, they applied Lagrange Multiplier unit root test that endogenously determines structural breaks, using official and black exchange rate data over 1970-1998. The empirical results indicated that the PPP holds for all countries when the test with two structural breaks is applied [35]. Al-Ahmad and Ismaiel examined the PPP using monthly data of the real effective exchange rates in 4 Arab countries, including Syria, from 1995 to 2014. For this purpose, the authors applied unit root tests that account for endogenous structural breaks in the data, those being the Zivot and Andrews test and the Lumsdaine and Papell tests. The results indicated that the unit root null hypothesis could be rejected for Syria only when the Lumsdaine and Papell three structural break test was applied and at the 10% level of significance [36].

The scarcity of research that focused on Syria during the recent period of crisis and the fact that the validity of the PPP hypothesis depends largely on the period of analysis, the type of data used and the econometric tests applied, motivated further testing of the PPP for this country.

The purpose of this study is to test the PPP hypothesis for Syria using more recent data that includes the recent crisis that erupted in 2011 in the context of unit root tests based on linear and non-linear models of the real exchange rate.

The current study makes three main contributions to the literature; first, it tests the validity of the PPP hypothesis by examining monthly real exchange rates of the Syrian pound against the US dollar over the period 2011:04-2020:08. This period is characterized by deterioration in the economic fundamentals and sharp currency depreciation as a result of the crisis that erupted on March 2011. Given developments in the official rate, the emergence of a parallel market, and a newly implemented intervention rate, the International Monetary Fund changed the classification of the exchange rate arrangement of Syria from “stabilized arrangement” to “other managed arrangement” on April 2011. Worth noting that Syria maintains during the period of study a multiple currency practice resulting from divergences of more than 2% between the official exchange rate and officially recognized market exchange rates [37].

Second, this study uses both the official and the parallel exchange rates in testing the PPP, which fills an important gap in the literature of PPP. In fact, studies concerning PPP mostly used the official exchange rates, especially in less developed countries. However, as outlined by Bahmani-Oskooee and Gelan, the official exchange rates may bias the inferences concerning the validity of PPP in the countries with significant black-market activities [21]. More specifically, due to restrictions on foreign currencies in Syria, these currencies are more expensive on the black market. The black-market or parallel exchange rate would thus reflect actual supply and demand pressures, and testing the validity of PPP in this context may indicate whether the foreign exchange market is efficient [38].

Third, in addition to conventional unit root tests, the nonlinear unit root tests of Kapetanios et al, Kruse, Kılıç and Sollis are applied to account for the possible nonlinearity that may arise from transaction costs, trade barriers and frequent official interventions in the foreign exchange market. As pointed out in Bahamani-Oskooee and Hegerty [38], nonlinear tests can be particularly useful in a study of less developed countries that face both external and internal shocks, such as periods of high inflation and sharp depreciation or devaluation of the exchange rate, which is the case of the Syrian economy. To our best knowledge, this study is the first that employs these nonlinear unit root tests to examine the validity of PPP for Syria over the period of crisis that erupted on March 2011.

The findings of this study should provide new evidence on the behavior of exchange rates in Syria during the recent period of crisis, which should be of interest to economists, policy makers and exchange rate market participants. As outlined by Taylor, the more important problem is to explain what drives the short-run dynamics of real exchange rates and how we account for the persistence of deviations from PPP in different time periods [39]. More specifically, knowing whether the PPP holds and if the real exchange rates follow a global stationary nonlinear process is important to specify the nature of chocks to the real exchange rate and the appropriate policy response.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data

To test the validity of PPP for Syria, the study applies monthly time series data of the natural logarithm of real exchange rate of the Syrian Pound against the US dollar from 2011:04 to 2020:08.

The importance of using the bilateral exchange rate against the dollar emerges from the fact that internal foreign exchange market is dollar dominated.

The real exchange rate is constructed as: RER =EX * (CPIUS / CPISY)

Where RER is the Real Exchange Rate, EX is the nominal Exchange Rate (measured as the price of the Syrian Pound relative to one unit of the US Dollar), and CPIUS and CPISY are the foreign and domestic consumer price indices (based on 2010=100), respectively.

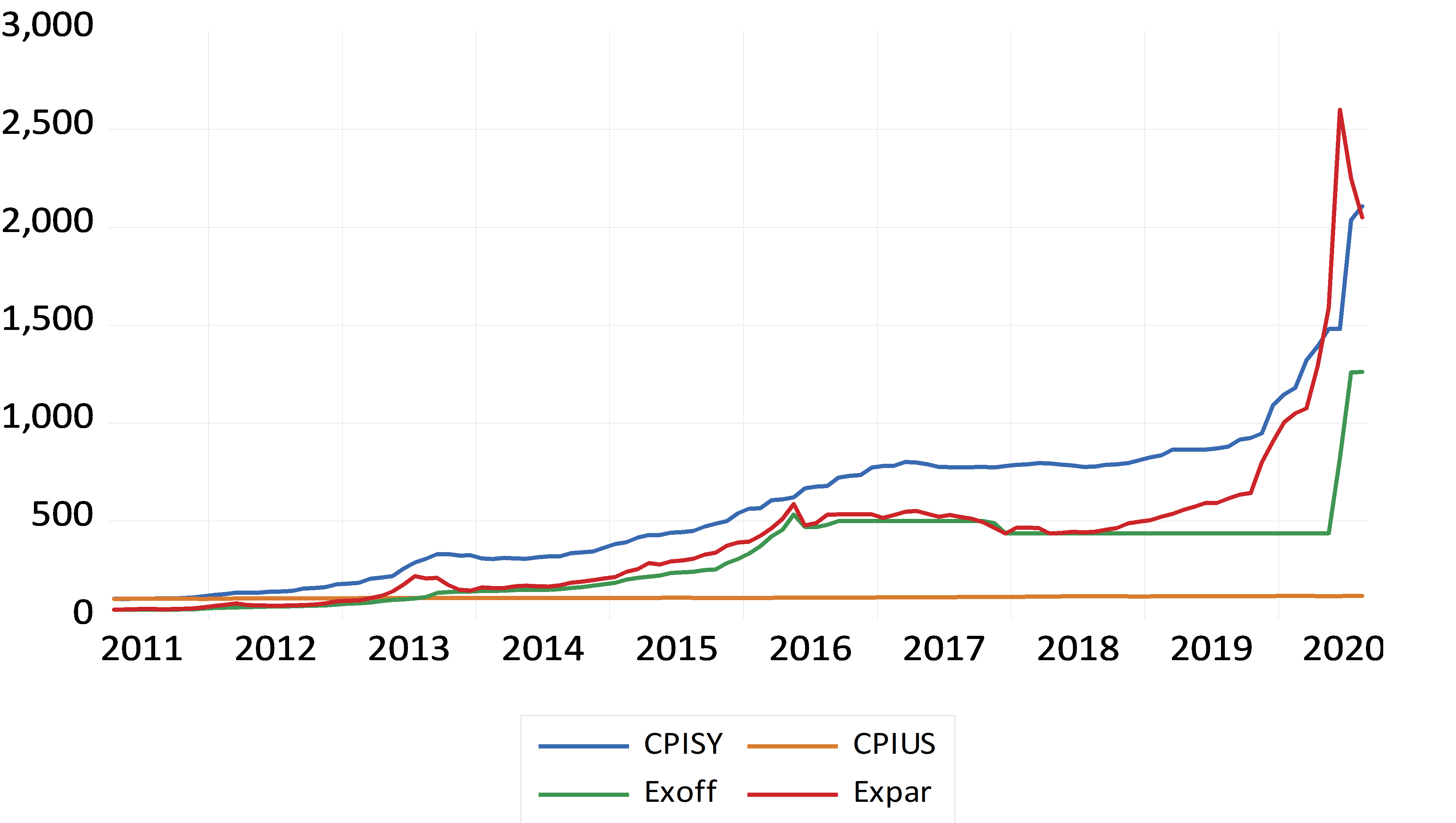

We use both the official as well as the parallel real exchange rates against the US dollar. The real official exchange rate (RERoff) is constructed using the nominal official exchange rate (EXoff), while the real parallel exchange rate (RERPar) is constructed using the nominal parallel exchange rate (EXPar). All the series are plotted in Figure 1.

Data of the nominal exchange rates and the CPISY were collected from the Central Bank of Syria CBS (Data of the nominal official exchange rate were collected from the CBS website (available at https://www.cb.gov.sy/index.php?page=list&ex=2&dir=exchangerate&lang=1&service=4&act=1207). Data of the nominal parallel exchange rate (2011-0ctobre 2019) were obtained from the CBS upon request. Data of CPISY (2010=100) were collected from the CBS website for the period (2014:01-2020:08) (available at https://www.cb.gov.sy/index.php?page=list&ex= 2&dir=publications&lang=1&service=4&act=565). Data of CPISY (2010=100) for the period (2011:04-2013:12) were obtained from the CBS upon request because available data at the website are based on (2005=100) for this period. Note that data of CPISY are not available after 2020:08.). Data of the CPIUS were collected from the International Monetary Fund (Available at https://data.imf.org/regular.aspx?key=61015892).

Methods

To test the presence of a unit root in the exchange rate series, conventional unit root tests without structural breaks (ADF and PP) are first applied. However, these tests don’t take into account the presence of structural breaks in the data. In order to capture the structural breaks in the data, we employ the Lee and Strazicich one and two break unit root tests based on LM test.

While conventional and breakpoint unit root tests are applied, the data is assumed to be linear. Therefore, Kapetanios et al, Kruse, Kılıç and Sollis nonlinear unit root tests are applied based on the smooth transition autoregressive (STAR) model.

The Lee and Strazicich tests

Lee and Strazicich proposed using a minimum Lagrange Multiplier LM test for testing the presence of a unit root with one and two structural breaks. For this purpose, two models are considered; model A which allows for structural break in the intercept under the alternative hypothesis, and model C which allows for structural break in both the intercept and trend under the alternative hypothesis.

Nonlinear unit root test of Kapetanios et al

Kapetanios et al developed a procedure to detect the presence of non-stationarity against nonlinear but globally stationary exponential smooth transition autoregressive ESTAR processes. To this end, the following specific ESTAR model is used [16]:

∆yt= γyt-1[1-exp(-өy2t-1)] +ℇt (1)

Where ө (the slope parameter) is zero under the null hypothesis of unit root and positive under the alternative hypothesis of the stationary ESTAR process. Kapetanios et al. (2003) use first-order Taylor series approximation to the ESTAR model under the null and get the following auxiliary regression:

∆yt=δY3t-1+error (2)

Noting that the demeaned data is used for the case with nonzero mean, and the demeaned and detrended data for the case with nonzero mean and nonzero linear trend.

Assuming that the errors in equation 1 are serially correlated and that they enter in a linear fashion, then Kapetanios et al. (2003) extend model (1) to:

∆yt= j∆yt-j+ γyt-1[1-exp(-өy2t-1)] +ℇt (3)

The null hypothesis is tested against the alternative hypothesis by the tNL statistic:

tNL= /s.e ( ) (4)

Where δ ̂is the OLS estimate of δ and (s.e ( )) is the standard error of ( ) obtained from the following regression with p augmentation [16]:

∆yt= j∆yt-j+ δy3t-1+error (5)

With δ ̂is zero under the null hypothesis of unit root and negative under the alternative hypothesis.

Nonlinear unit root test of Kruse

Kruse extended the unit root test of Kapetanios et al by allowing for a nonzero attractor c in the exponential transition function. The degree of mean reversion of the real exchange rate depended on the distance of the lagged real exchange rate from this attractor [9].

To this end, he considers the following nonlinear time series model:

∆yt= γyt-1(1-exp {-ө (yt-1-c )2}) +ℇt (6)

As in Kapetanios et a, Kruse applied a first- order Taylor approximation around ө=0, and imposes β3 =0. The following regression was hence obtained:

∆yt= β1y3t-1+ β2y2t-1 +ut (7)

With ut being a noise term depending on ℇt.

In the regression 7, the null hypothesis of a unit root was H0: β1 = β2 = 0 and the alternative hypothesis of a globally stationary ESTAR process was H1: β1 < 0, β2 ≠ 0. Note that a standard Wald test wasn’t appropriate as one parameter is one-sided under H1 while the other one is two-sided [19]. To overcome this problem, Krus drived a modified Wald test that built up on the inference techniques by Abadir and Distaso [40]:

Ί=t2ß1/2=0+1( ˂0) t2ß1=0 (8)

Where t2ß1/2=0 represents the squared t-statistic for the hypothesis ß1/2= 0 with ß1/2 being orthogonal to β1. The second term t2ß1 is a squared t-statistic for the hypothesis β1 = 0.

Nonlinear unit root test of Kılıç

Kılıç considered an ESTAR model where the transition variable was the lagged changes of the dependent variable. Once appreciations or depreciations were large enough, real exchange rates may adjust towards equilibrium level due to profitable arbitrage.

The unit root test proposed was based on a one-sided t statistic where the t-statistic was optimized over the transition parameter space (γ). Kılıç specifies the following model, under the assumption that serially correlated errors entered in a linear way [24]:

∆yt= i∆yt-i+ Φyt-1[1-exp(-γz2t)] +ℇt (9)

With: Zt= ∆yt-d

The null and alternative hypotheses were set as H0: Φ= 0 against H1: Φ< 0.

As γ was unidentified under the unit root null hypothesis, Kılıç suggested to use the lowest possible t-value over a fixed parameter space of γ values that were normalized by the sample standard deviation of the transition variable zt.

Nonlinear unit root test of Sollis

ESTAR models assumed symmetrical adjustment in exchange rates towards PPP for the same size of a deviation, regardless of whether the real exchange rate was below or above the mean. However, appreciations and depreciations may lead to different speed of adjustment towards PPP [25].

Sollis proposed a test based on asymmetric exponential smooth transition autoregressive (AESTAR), where the speed of adjustment could be different below or above the threshold band.

The extended ESTAR process was as follows [25]:

∆yt=Φ1 y3t-1+Φ2 y4t-1+ i∆yt-i+ηi (10)

In the case of the rejection of the unit root hypothesis (Φ1= Φ2=0), the symmetric hypothesis, (Φ2=0) will be tested against the asymmetric alternative hypothesis, Φ2≠ 0. The hypothesis may be tested for the zero mean, non-zero mean and deterministic trend cases.

RESULTS

Prior to applying the nonlinear unit root tests, conventional linear unit root tests, which do not take into account any structural breaks, are first used. We initially employ the Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) and the Phillips and Perron (PP). The null hypothesis is a unit root for these two tests.

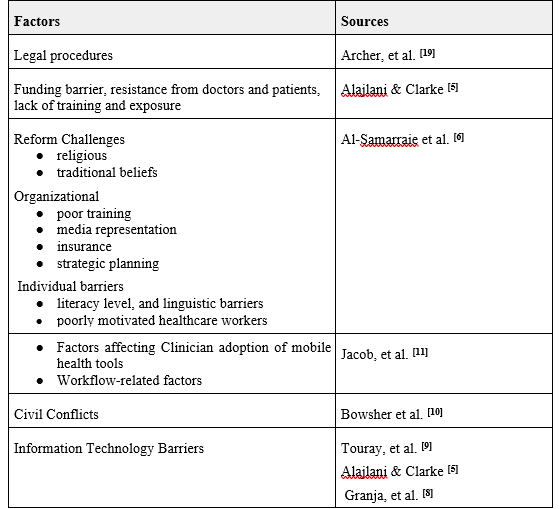

The findings, presented in Table 1, indicate the random walk behavior of both the official and the parallel exchange rates series.

| Table 1: Conventional Linear Unit Root Tests Results | ||||

| ADF | PP | |||

| Constant | Constant and trend | Constant | Constant and trend | |

| LRERoff | -1.95 (0) | -2.28 (0) | -2.09 (2) | -2.29 (0) |

| LRERpar | -0.60 (3) | -1.96 (3) | -1.48 (7) | -3.03 (3) |

Source: Own computation (E-Views)

Notes: The lag length of the tests are reported in brackets. The optimal lag length of the ADF test was selected based on the modified AIC (MAIC). The bandwidth for the PP test were selected based on Newey-West automatic bandwidth selection procedure for a Bartlett kernel. The critical values for ADF and PP tests are -3.49 (1%), -2.89 (5%) and -2.58 (10%) for model with constant; and -4.05 (1%), -3.45 (5%) and -3.15 (10%) for the model with constant and trend.

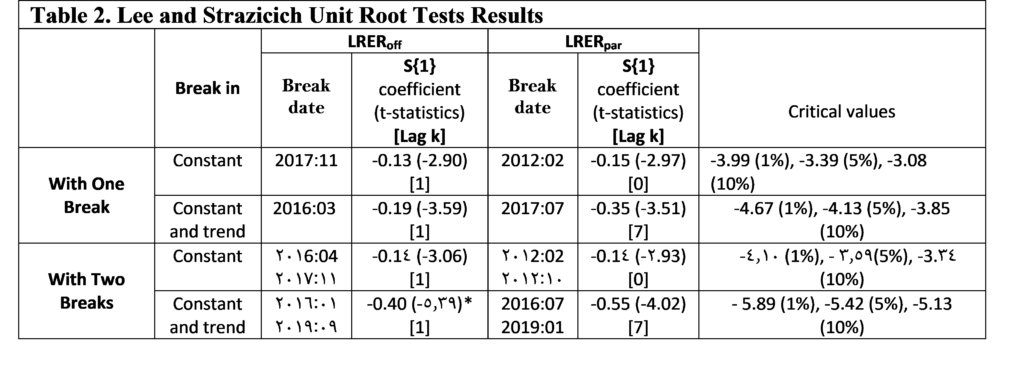

To account for the power loss in the presence of structural breaks, we employ the Lee and Strazicich one and two break unit root tests. The relevance of using this approach is that it is unaffected by breaks under the null. According to the results reported in Table 2, we cannot reject the null hypothesis at the 5% level of significance, regardless of whether we use official or parallel official exchange rates. The null hypothesis could be rejected only for the official exchange rate after allowing for two breaks in the constant and trend and at the 10% level of significance. Note that the estimated break dates appear to vary concerning the model specification and data used.

These findings are consistent with those of Al-Ahmad and Ismaiel [36], who found that the unit root null hypothesis of Lumsdaine and Papell test could be rejected for the real effective exchange rates of the Syrian Pound only after allowing for three changes in the constant and trend and at the 10% level of significance.

Source: Own computation (E-Views)

Source: Own computation (E-Views)

Notes: The coefficient of S{1} tests for the unit-root. The T-statistics are reported in brackets. The optimal lag length is determined by GTOS method. ***, **, * denote rejection of the null hypothesis of a unit root at 1%, 5% and 10% level of significance respectively.

We now test whether taking into account for non-linearity in the real exchange rates plays a role in analyzing unit root dynamics. Prior to this, we checked the nonlinearity of the series by using the conventional BDS test proposed by Broock et al [41]. According to the results, a nonlinear nature was detected in both series, which makes relevant to apply nonlinear unit root test (Results from the BDS test are not presented here but available upon request). To this end, we proceed with the non-linear unit root tests developed by Kapetanios et al. (2003), Kruse (2011), Kılıç (2011) and Sollis (2009). The results of test statistics are reported in Table 3.

| Table 3: Nonlinear Unit Root Tests Results | ||||||

| The nonlinear unit root test | LRERoff | LRERpar | Critical values | |||

| 1% | 5% | 10% | ||||

| Kapetanios et al. (2003) | Demeaned data | -5.82***(1) | -5.03***(1) | -3.48 | -2.93 | -2.66 |

| Detrended data | -6.58***(1) | -6.83***(1) | -3.93 | -3.40 | -3.13 | |

| Sollis (2009) | Demeaned data | 25.74***(1) | 16.51***(1) | 6.89 | 4.88 | 4.00 |

| Detrended data | 22.62 ***(1) | 23.18***(1) | 8.80 | 6.55 | 5.41 | |

| Kılıç (2011) | Demeaned data | -2.23*(1) | -1.58 (1) | -2.98 | -2.37 | -2.05 |

| Detrended data | -2.61**(1) | -2.99**(1) | -3.19 | -2.57 | -2.23 | |

| Kruse (2011) | Demeaned data | 44.35***(1) | 33.24***(1) | 13.75 | 10.17 | 8.60 |

| Detrended data | 42.97***(1) | 47.47***(1) | 17.10 | 12.82 | 11.10 | |

Source: Own computation (R for windows)

Notes: The lag length of the tests are reported in brackets. For all tests, the order of lags was chosen according to the Akaike information criterion (AIC). Table critical values of unit root tests are taken from KSS (2003)[16], Sollis (2009)[25], Kılıç (2011)[24] and Kruse (2011)[19]. ***, **, * denote rejection of the null hypothesis of a unit root at 1%, 5% and 10% level of significance respectively.

The results of Kapetanios et al and Kruse showed that the null of unit root was rejected at the 1% level of significance for both official and parallel exchange rate, regardless of whether we use model with demeaned or detrended data. We also rejected the null hypothesis for both series at the 1% level of significance of the (AESTAR) model of Sollis.

The test of Kılıç rejects the null hypothesis at the 5% level of significance for only the detrended data of both series. When demeaned data was used, the null of unit root test of Kılıç was rejected for only the official exchange rate and at the 10% level of significance. The test of

Kılıç hence provides stronger empirical support for nonlinear stationarity of the official exchange rate compared to parallel exchange rate. Non-linearity in the official exchange rates may rise, as suggested by Bahmani-Oskooee et al [42], from structural breaks due to official devaluation, besides frequent official interventions.

We note that Kılıç, which associates nonlinearity with the size of real exchange rate appreciation or depreciation, provided less evidence in favor of PPP compared to Kapetanios et al and Kruse, which allow for nonlinearity driven by the size of deviations from PPP. This finding contrasts with that of Yıldırım who found that the strongest evidence for PPP in Turkey is obtained through the unit root test of Kılıç [9].

DISCUSSION

Transaction costs and trade barriers are the plausible sources of nonlinearity in real exchange rates during the period of the study. It is important to note that the imposition of financial and economic sanctions has restricted exports and imports in Syria. (These sanctions include the freezing of Government of Syria assets, the cessation of transactions with individuals and companies in Syria, the termination of all investments supported by foreign Governments and the banning imports of Syrian oil). Indeed, the great government spending on nontraded goods compared to traded goods during the period of crisis has increased the share of nontraded goods.

The nonlinearity of exchange rate series may also arise from frequent official interventions in the foreign exchange market. In fact, the continuous deterioration in the economic fundamentals, in addition to the speculative pressure and the capital flight have contributed to sharp depreciation of the Syrian pound during the period of crisis, which authority tried to counter through increasing the interventions. These interventions could lead to non-linearity into the adjustment of the nominal exchange rate and, with price stickiness in the short run, the adjustment of the real exchange rate as well [1,42]. Note that, as stated in Dutta and Leon [43], policymakers in less developed countries prefer having longer periods of currency appreciation than depreciation, even though the economic fundamentals would require the opposite. This could be explained by fear of inflation (pass-through from exchange rate swings to inflation) and currency mismatches.

The high level of inflation could be another possible contributor to adjustment of real exchange rates series. The annual inflation rate in Syria reached 163.1% in December 2020 compared to the base year 2010, the year before the eruption of the Syrian crisis [44]. This implies, as argued by Cashin and Mcdermott [34], more frequent adjustment of goods prices, which could reduce the duration of deviation from PPP. Note that as prices have less of a tendency to move downwards, the exchange rate might have to do more of the adjusting. An adjustment might thus be asymmetric between the upward and downward deviations from equilibrium [38].

Our results can also provide some evidence on how the monetary authority in Syria reacted in the period of crisis. According to IFM reports, the exchange rate classification of Syria was changed from “stabilized arrangement” to “other managed management” on April 2011, in the aftermath of the crisis that erupted on March 2011 [37]. This means moving to more flexible exchange rate regime. In 2012, the prime minister issued the law No. 1131 which stated the movement towards a free exchange rate regime, with the right of the Central Bank of Syria to intervene in the exchange market to correct the exchange rate trends in the market. We believe that moving to a more market-oriented exchange rate has facilitated the nominal exchange rate adjustment. As discussed in Cashin and Mcdermott [34], more flexibility in nominal exchange rates may increase the speed of the parity reversion of real exchange rates by encouraging more frequent adjustment of goods prices. These findings are consistent with those of Baharumshah et al, as they found that the weak form of PPP holds for six East-Asian countries only over the post-crisis period [45]. They suggest that the evidence in favor of PPP was stronger following the financial crisis when countries had to abandon pegging their exchange rates. We also believe that interventions in the foreign exchange market have some justification as the deviations of real exchange rates from the equilibrium appear to be temporary and the exchange rates are adjustable towards PPP.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATION

This study investigates the PPP hypothesis for Syria over the period (2011:04-2020:08), using both official and parallel real exchange rates of the Syrian Pound against the US Dollar. To this end, a battery of nonlinear unit root tests is adopted along with popular conventional unit root tests.

The conventional tests (ADF and PP) fail to reject the null of a unit root for the real exchange rate series at the 5% level of significance, regardless of whether we use official or parallel exchange rate. The non-stationarity of both series is robust to the existence of breaks since the Lee and Strazicich unit root tests fail to reject the null hypothesis at the 5% level of significance for both official and parallel series.

When nonlinearity is incorporated in the testing procedure, the nonlinear tests of Kapetanios et al, Kruse, and Sollis support PPP for both real exchange rate series under consideration at the 1% level of significance. The test of Kılıç supports PPP only after allowing for a trend in both series and at the 5% level of significance.

The findings of this study provide new evidence on the behavior of exchange rates in Syria during the recent period of crisis. The non-linear mean reversion indicates that as the real exchange rate deviates from its long-run equilibrium, it tends to have faster speed of adjustment. This implies that PPP can be used to determine whether the currency is overvalued or undervalued, and investors and speculators are not able to obtain unbounded gains from arbitrage [9,45].

Finally, as our results signify the importance of non-linear adjustment in real exchange rates, it is so important that policymakers and exchange rate market participants take account of possibility of nonlinear dynamics in their decisions. Future research should also take on the issue of nonlinearity of real exchange rate more seriously when examining the PPP.

For many decades, the majority of Arab countries relied mainly on natural resources as their economy-driving engine, being rather late in adapting policies and practices promoting knowledge-based economies, and have a limited industrial base. Today however, it is quite obvious that leading states are those whose decision-making hubs have intensively invested in their national intellectual capita, promoting knowledge and technology transfer; enhancing training, R&D, and innovation activities. This is extremely crucial, as both local and global markets are prone to rapid technological changes, demanding academics and researchers with elevated level of expertise and highly skilled labor force. Explicitly, the contemporary development of a state is determined not by scaling up the use of its natural resources but by endorsing intangible human capital as the basis for continuous development of technologies and innovation.

Human capital is defined as the knowledge, education and competencies of individuals in realizing national tasks and goals. The human capital of a nation originates with the intellectual wealth of its citizens, usually measured by National Intellectual Capital Index (NICI). Even though policy makers sometimes find it hard to make the case for human capital investments due to lack of quick returns, there is rather a unified understanding about the importance of knowledge as a source of economic competitiveness.

Compared to many Arab countries, the situation is far more complicated in Syria after approximately twelve years of war and conflict, where natural resources became scarce and manufactured good exports, reflected in gross domestic product (GDP), drastically declined. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic, the Russian-Ukrainian conflict that started in 2022, and finally the recent earthquake that hit Syria and Turkey last February, all severely augmented the conflict consequences.

Nevertheless, and since 1950s, Syria has been known for highly educated graduates in both engineering and life sciences who contributed to science advancement in Syria and the region. Additionally, Syrian expatriate medical doctors, researchers and engineers gained respectable reputation for their service and academic contributions all over the world. In fact, during the last two decades, Syria sent abroad thousands of academic envoys to support the Syrian academic and research ecosystem upon their return. Unfortunately, very few of them returned home due to circumstances enforced by the recent conflict and the deterioration of the Syrian economy. Taken together, Syria has a good opportunity to benefit from its national human capita if solid and serious steps are taken and followed up.

On one hand, reforms on education and training policies should be accomplished to raise national standards of knowledge and skill transfer among Syrian youth and university postgraduate students and researchers. This should be accompanied by boosting technology transfer activities via intermediaries such as the National Technology Transfer Office NTTO (hosted by the Higher Commission for Scientific Research, HCSR) and other institutional TTOs at both public and private Syrian universities and research centers. On the other hand, the Syrian government officials and decision-makers are requested to find the proper channels to communicate with Syrian expats and benefit from the knowledge and expertise they gain while living in foreign countries. The Syrian Expatriate Research Conference (SERC), which is organized annually by HCSR, is one tool to achieve fruitful interactions among Syrian researchers at home and abroad. Another two relevant ways include preparing a national strategy and roadmap for enhancing cooperation and coordination with Syrian expat researchers, and creating incentive programs similar to international programs such as the “Chinese Academy of Science’s 100 Talents Program”.

For countries like Syria, taking into account the dwindle in natural resources and the shrink in national economy, investing in intellectual human capita should be listed among the highest Syrian government priorities … it is a MUST.

INTRODUCTION

Nowcasting refers to the projection of information about the present, the near future, and even the recent past. The importance of nowcasting has shifted from weather forecasting to economics, where economists use it to track the economy status through real-time GDP forecasts, as it is the main low-frequency (quarterly – annually) indicator reflecting the state of the country’s economy. This is like satellites that reflect the weather on earth. It does this by relying on high-frequency measured variables (daily – monthly) that are reported in real-time. The importance of using nowcasting in the economy stems from the fact that data issuers, statistical offices and central banks release the main variables of the economy, such as gross domestic product and its components, with a long lag. In some countries, it may take up to five months. In other countries, it may take two years depending on the capabilities each country has, leading to a state of uncertainty about the economic situation among economic policy makers and state followers business. Real-time indicators related to the economy (e.g consumer prices and exchange rates) are used here in order to obtain timely information about variables published with a delay. The first use of nowcasting technology in economics dates back to Giannone et al 2008, by developing a formal forecasting model that addresses some of the key issues that arise when using a large number of data series released at varying times and with varying delays [1]. They combine the idea of “bridging” the monthly information with the nowcast of quarterly GDP and the idea of using a large number of data releases in a single statistical framework. Banbura et al proposed a statistical model that produces a series of Nowcasting forecasts on real-time releases of various economic data [2]. The methodology enables the processing of a large amount of information from nowcasting’s Eurozone GDP Q4 2008 study. Since that time, the models that can be used to create nowcasting have expanded. Kuzin et al compared the mixed-frequency data sampling (MIDAS) approach proposed by Ghysels et al [4,5] with the mixed-frequency VAR (MF-VAR) proposed by Zadrozny and Mittnik et al [6,7], with model specification in the presence of mixed-frequency data in a policy-making situation, i.e. nowcasting and forecasting quarterly GDP growth in Eurozone on a monthly basis. After that time, many econometric models were developed to allow the use of nowcasting and solve many data problems. Ferrara et al [8] proposed an innovative approach using nonparametric methods, based on nearest neighbor’s approaches and on radial basis function, to forecast the monthly variables involved in the parametric modeling of GDP using bridge equations. Schumacher et al [9] compare two approaches from nowcasting GDP: Mixed Data Sampling (MIDAS) regressions and bridge equations. Macroeconomics relies on increasingly non-standard data extracted using machine learning (text analysis) methods, with the analysis covering hundreds of time series. Some studies examined US GDP growth forecasts using standard high-frequency time series and non-standard data generated by text analysis of financial press articles and proposed a systematic approach to high-dimensional time regression problems [10-11]. Another team of researchers worked on dynamic factor analysis models for nowcasting GDP [12], using a Dynamic Factor Model (DFM) to forecast Canadian GDP in real-time. The model was estimated using a mix of soft and hard indices and the authors showed that the dynamic factor model outperformed univariate criteria as well as other commonly used nowcasting models such as MIDAS and bridge regressions. Anesti et al [13] proposed a release-enhanced dynamic factor model (RA-DFM) that allowed quantifying the role of a country’s data flow in the nowcasting of both early (GDP) releases and later revisions of official estimates. A new mixed-frequency dynamic factor model with time-varying parameters and random fluctuations was also designed for macroeconomic nowcasting, and a fast estimation algorithm was developed [14]. Deep learning models also entered the field of GDP nowcasting, as in many previous reports [15-17]. In Syria, there are very few attempts to nowcasting GDP, among which we mention a recent report that uses the MIDAS Almon Polynomial Weighting model to nowcasting Syria’s annual GDP based on the monthly inflation rate data [18]. Our research aims to solve a problem that exists in the Arab and developing countries in general, and Syria in particular, namely the inability to collect data in real-time on the main variable in the economy due to the weakness of material and technical skills. Therefore, this study uses Bayesian mixed-frequency VAR models to nowcast GDP in Syria based on a set of high-frequency data. The rationale for choosing these models is that they enable the research goal to be achieved within a structural economic framework that reduces statistical uncertainty in the domain of high-dimensional data in a way that distinguishes them from the nowcasting family of models, according to a work by Cimadomo et al and Crump et al [19-20]. The first section of this research includes the introduction and an overview of the previous literature. The second section contains the research econometric framework, through which the architecture of the research model is developed within a mathematical framework. The third section is represented by the data used in the research including the exploratory phase. The fourth section contains the discussion and interpretation of the results of the model after the evaluation. The fifth section presents the results of the research and proposals that can consider a realistic application by the authorities concerned.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The working methodology in this research is divided into two main parts. The first in which the low-frequency variable (Gross Domestic Product) is converted from annual to quarterly with the aim of reducing the forecast gap and tracking the changes in the GDP in Syria in more real-time., by reducing the gap with high-frequency data that we want to predict their usage. To achieve this, we used Chow-Lin’s Litterman: random walk variant method.

Chow-Lin’s Litterman Method

This method is a mix and optimization of two methods. The Chow-Lin method is a regression-based interpolation technique that finds values of a series by relating one or more higher-frequency indicator series to a lower-frequency benchmark series via the equation:

x(t)=βZ(t)+a(t) (1)

Where is a vector of coefficients and a random variable with mean zero and covariance matrix Chow and Lin [21] used generalized least squares to estimate the covariance matrix, assuming that the errors follow an AR (1) process, from a state space model solver with the following time series model:

a(t)=ρa(t-1)+ϵ(t) (2)

Where ϵ(t)~N(0,σ^2) and |ρ|<1. The parameters ρ and βare estimated using maximum likelihood and Kalman filters, and the interpolated series is then calculated using Kalman smoothing. In the Chow-Lin method, the calculation of the interpolated series requires knowledge of the covariance matrix, which is usually not known. Different techniques use different assumptions about the structure beyond the simplest (and most unrealistic) case of homoscedastic uncorrelated residuals. A common variant of Chow Lin is Litterman interpolation [22], in which the covariance matrix is computed from the following residuals:

a(t)=a(t-1)+ϵ(t) (3)

Where ϵ(t)~N(0,V)

ϵ(t)=ρϵ(t-1)+e(t) (4)

and the initial state a(0)=0. . This is essentially an ARIMA (1,1,0) model.

In the second part, an econometric model suitable for this study is constructed by imposing constraints on the theoretical VAR model to address a number of statistical issues related to the model’s estimation, represented by the curse of dimensions.

Curse of Dimensions

The dimensional curse basically means that the error increases with the number of features (variables). A higher number of dimensions theoretically allows more information to be stored, but rarely helps as there is greater potential for noise and redundancy in real data. Collecting a large number of data can lead to a dimensioning problem where very noisy dimensions can be obtained with less information and without much benefit due to the large data [23]. The explosive nature of spatial scale is at the forefront of the Curse of Dimensions cause. The difficulty of analyzing high-dimensional data arises from the combination of two effects: 1- Data analysis tools are often designed with known properties and examples in low-dimensional spaces in mind, and data analysis tools are usually best represented in two- or three-dimensional spaces. The difficulty is that these tools are also used when the data is larger and more complex, and therefore there is a possibility of losing the intuition of the tool’s behavior and thus making wrong conclusions. 2- The curse of dimensionality occurs when complexity increases rapidly and is caused by the increasing number of possible combinations of inputs. That is, the number of unknowns (parameters) is higher than the number of observations. Assuming that m denotes dimension, the corresponding covariance matrix has m (m+1)/2 degrees of freedom, which is a quadratic term in m that leads to a high dimensionality problem. Accordingly, by imposing a skeletal structure through the initial information of the Bayesian analysis, we aimed to reduce the dimensions and transform the high-dimensional variables into variables with lower dimensions and without changing the specific information of the variables. With this, the dimensions were reduced in order to reduce the feature space considering a number of key features.

Over Parameterizations

This problem, which is an integral part of a high dimensionality problem, is statistically defined as adding redundant parameters and the effect is an estimate of a single, irreversible singular matrix [24]. This problem is critical for statistical estimation and calibration methods that require matrix inversion. When the model starts fitting the noise to the data and the estimation parameters, i.e. H. a high degree of correlation existed in the co-correlation matrix of the residuals, thus producing predictions with large out-of-sample errors. In other words, the uncertainty in the estimates of the parameters and errors increases and becomes uninterpretable or far from removed from the realistic estimate. This problem is addressed by imposing a skeletal structure on the model, thereby transforming it into a thrift. Hence, it imposes constraints that allow a correct economic interpretation of the variables, reducing the number of unknown parameters of the structural model, and causing a modification of the co – correlation matrix of the residuals so that they become uncorrelated with some of them, in other words, become a diagonal matrix.

Overfitting and Underfitting

Overfitting and Underfitting are major contributors to poor performance in models. When Overfitting the model (which works perfectly on the training set while ineffectively fitting on the test set), it begins with matching the noise to the estimation data and parameters, producing predictions with large out-of-sample errors that adversely affect the model’s ability to generalize. An overfit model shows low bias and high variance [25]. Underfitting refers to the model’s inability to capture all data features and characteristics, resulting in poor performance on the training data and the inability to generalize the model results [26]. To avoid and detect overfitting and underfitting, we tested the validity of the data by training the model on 80% of the data subset and testing the other 20% on the set of performance indicators.

Theoretical VAR model

VAR model developed by Sims [27] has become an essential element in empirical macroeconomic research. Autoregressive models are used as tools to study economic shocks because they are based on the concept of dynamic behavior between different lag values for all variables in the model, and these models are considered to be generalizations of autoregressive (AR) models. The p-rank VAR is called the VARp model and can be expressed as:

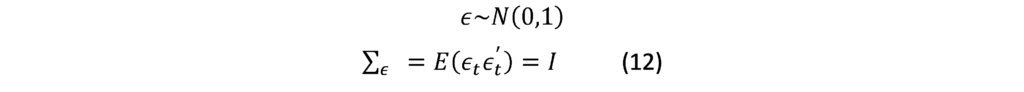

y_t=C+β_1 y_(t-1)+⋯+β_P y_(t-P)+ϵ_t ϵ_t~(0,Σ) (5)

Where y_t is a K×1 vector of endogenous variables. Is a matrix of coefficients corresponding to a finite lag in, y_t, ϵ_t: random error term with mean 0 representing external shocks, Σ: matrix (variance–covariance). The number of parameters to be estimated is K+K^2 p, which increases quadratic with the number of variables to be included and linearly in order of lag. These dense parameters often lead to inaccuracies regarding out-of-sample prediction, and structural inference, especially for high-dimensional models.

Bayesian Inference for VAR model

The Bayesian approach to estimate VAR model addresses these issues by imposing additional structure on the model, the associated prior information, enabling Bayesian inference to solve these issues [28-29], and enabling the estimation of large models [2]. It moves the model parameters towards the parsimony criterion and improves the out-of-sample prediction accuracy [30]. This type of contraction is associated with frequentist regularization approaches [31]. Bayesian analysis allows us to understand a wide range of economic problems by adding prior information in a normal way, with layers of uncertainty that can be explained through hierarchical modelling [32].

Prior Information

The basic premise for starting a Bayesian analysis process must have prior information, and identifying it correctly is very important. Studies that try not to impose prior information result in unacceptable estimates and weak conclusions. Economic theory is a detailed source of prior information, but it lacks many settings, especially in high-dimensional models. For this reason, Villani [33] reformulates the model and places the information at a steady state, which is often the focus of economic theory and which economists better understand. It has been proposed to determine the initial parameters of the model in a data-driven manner, by treating them as additional parameters to be estimated. According to the hierarchical approach, the prior parameters are assigned to hyperpriors. This can be expressed by the following Bayes law:

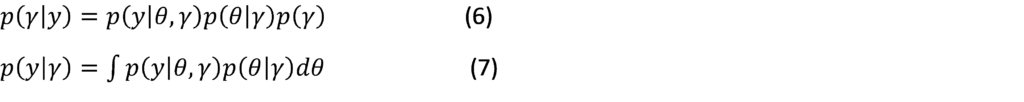

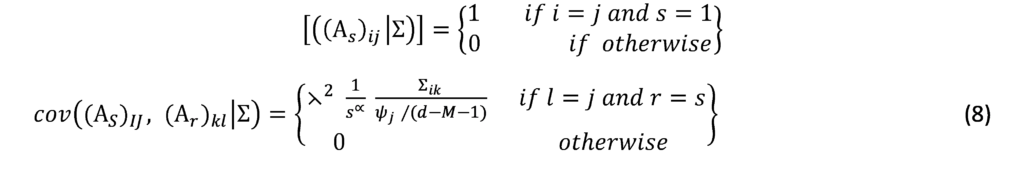

Wherey= (y_(p+1)+⋯+y_T)^T,θ: is coefficients AR and variance for VAR model, γ: is hyperparameters. Due to the coupling of the two equations above, the ML of the model can be efficiently calculated as a function of γ. Giannone et al [34] introduced three primary information designs, called the Minnesota Litterman Prior, which serves as the basis, the sum of coefficients [35] and single unit root prior [36].

Minnesota Litterman Prior

Working on Bayesian VAR priors was conducted by researchers at the University of Minnesota and the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis [37] and these early priors are often referred to as Litterman prior or Minnesota Prior. This family of priors is based on assumption that Σ is known; replacing Σwith an estimate Σ. This assumption leads to simplifications in the prior survey and calculation of the posterior.

The prior information basically assumes that the economic variables all follow the random walk process. These specifications lead to good performance in forecasting the economic time series. Often used as a measure of accuracy, it follows the following torques:

The key parameter ⋋ is which controls the magnitude influence of the prior distribution, i.e. it weighs the relative importance of the primary data. When the prior distribution is completely superimposed, and in the case of the estimate of the posterior distributions will approximate the OLS estimates. is used to control the break attenuation, and is used to control the prior standard deviation when lags are used. Prior Minnesota distributions are implemented with the goal of de-emphasizing the deterministic component implied by the estimated VAR models in order to fit them to previous observations. It is a random analysis-based methodology for evaluating systems under non-deterministic (stochastic) scenarios when the analytical solutions are complex, since this method is based on sampling independent variables by generating phantom random numbers.

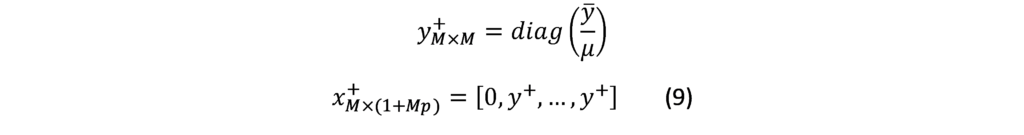

Dummy Observations

Starting from the idea of Sims and Zha [38] to complement the prior by adding dummy observations to the data matrices to improve the predictive power of Bayesian VAR. These dummy observations consist of two components; the sum-of-coefficient component and the dummy-initial-observation component. The sum-of-coefficients component of a prior was introduced by Doan et al [37] and demonstrates the belief that the average of lagged values of a variable can serve as a good predictor of that variable. It also expresses that knowing the average of lagged values of a second variable does not improve the prediction of the first variable. The prior is constructed by adding additional observations to the top (pre-sample) of the data matrices. Specifically, the following observations are constructed:

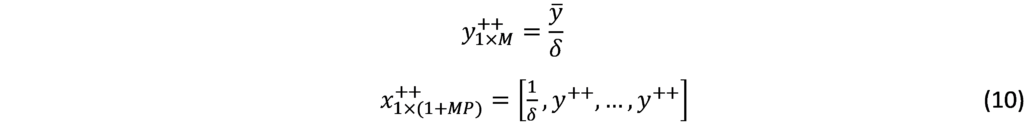

Where is the vector of the means over the first observed by each variable, the key parameter is used to control for variance and hence the impact of prior information. When the prior information becomes uninformative and when the model is formed into a formula consisting of a large number of unit roots as variables and without co-integration. The dummy initial observation component [36] creates a single dummy observation that corresponds to the scaled average of the initial conditions, reflecting the belief that the average of the initial values of a variable is likely to be a good prediction for that variable. The observation is formed as:

Where is the vector of the means over the first observed by each variable, the key parameter is used to control on variance and hence the impact of prior information. As , all endogenous variables in VAR are set to their unconditional mean, the VAR exhibits unit roots without drift, and the observation agrees with co-integration.

Structural Analysis

The nowcasting technique within the VAR model differs from all nowcasting models in the possibility of an economic interpretation of the effect of high-frequency variables on the low-frequency variable by measuring the reflection of nonlinear changes in it, which are defined as (impulse and response). A shock to the variable not only affects the variable directly, but it is also transmitted to all other endogenous variables through the dynamic (lag) structure of VAR. An impulse response function tracks the impact of a one-off shock to one of the innovations on current and future values of the endogenous variable.

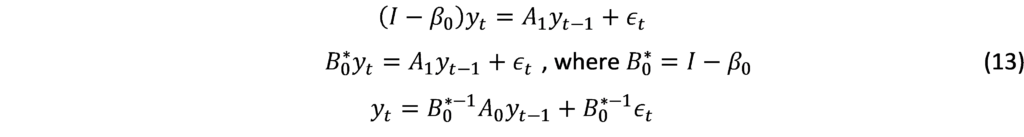

BVAR is estimated reductively, i.e., without a contemporary relationship between endogenous variables in the system. While the model summarizes the data, we cannot determine how the variables affect each other because the reduced residuals are not orthogonal. Recovering the structural parameters and determining the precise propagation of the shocks requires constraints that allow a correct economic interpretation of the model, identification constraints that reduce the number of unknown parameters of the structural model, and lead to a modification of the co-correlation matrix of the residuals so that they become uncorrelated, i.e., they become a diagonal matrix. This problem is solved by recursive identification and achieved by Cholesky’s analysis [39] of the variance and covariance matrix of the residuals , Where Cholesky uses the inverse of the Cholesky factor of the residual covariance matrix to orthogonalize the impulses. This option enforces an ordering of the variables in the VAR and attributes the entire effect of any common component to the variable that comes first in the VAR system. For Bayesian frame, Bayesian sampling will use a Gibbs or Metropolis-Hasting sampling algorithm to generate draws from the posterior distributions for the impulse. The solution to this problem can be explained mathematically from the VAR model:

![]()

Where show us contemporaneous correlation. Coefficient matrix at lag1, error term where:

In order to estimate the previous equation, we must abandon the contemporaneous relations between the endogenous variables since we transfer them to the other side:

Now parsimony VAR model can be estimated:

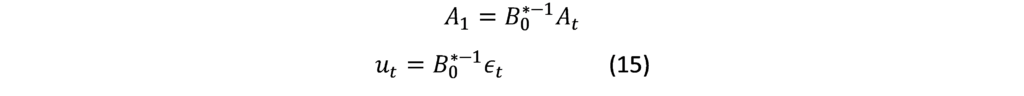

![]()

Where A_1 are reduced coefficient. u_t Represent the weighted averages of the structural coefficientsβ_1,ϵ_t. Where:

Mixed Frequency VAR

Mixed Frequency VAR

Complementing the constraints imposed on the theoretical VAR model, as a prelude to achieving the appropriate form for the research model and developing the model presented by AL-Akkari and Ali [40] to predict macroeconomic data in Syria, we formulate the appropriate mathematical framework for the possibility to benefit from high-frequency data emitted in real-time in nowcasting of GDP in Syria.

We estimate a mixed frequency VAR model with no constant or exogenous variables with only two data frequencies, low and high (quarterly-monthly), and that there are high frequency periods per low frequency period. Our model consists of variable observed at low frequency and variables observed at high frequency. Where:

: represent the low-frequency variable observed during the low-frequency period .

: represent the high-frequency variable observed during the low-frequency period .

By stacking the and variables into the matrices and ignoring the intersections and exogenous variables for brevity, respectively, we can write the VAR:

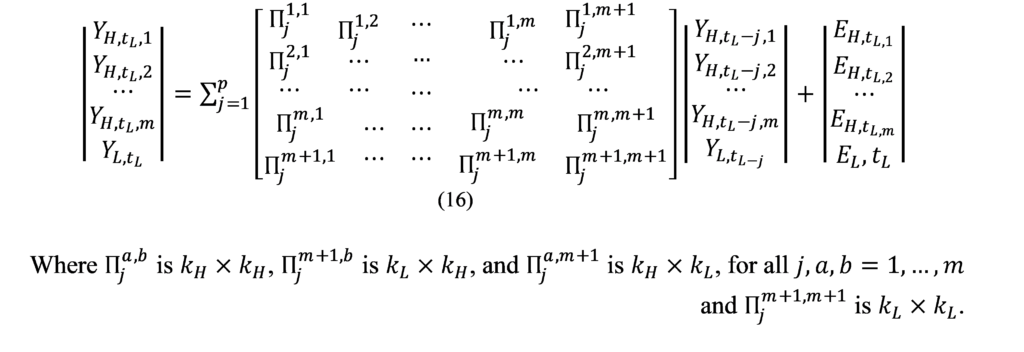

Performance indicators

We use indicators to assess the performance of the models which are used to determine their ability to explain the characteristics and information contained in the data. It does this by examining how closely the values estimated from the model correspond to the actual values, taking into account the avoidance of an underfitting problem that may arise from the training data and an overfitting problem that arises from the test data. The following performance indicators include:

Theil coefficient (U):

Mean Absolute Error (MAE):

Mean Absolute Error (MAE):![]()

Root Mean Square Error (RMSE):

Where the forecast is value; is the actual value; and is the number of fitted observed. The smaller the values of these indicators, the better the performance of the model.

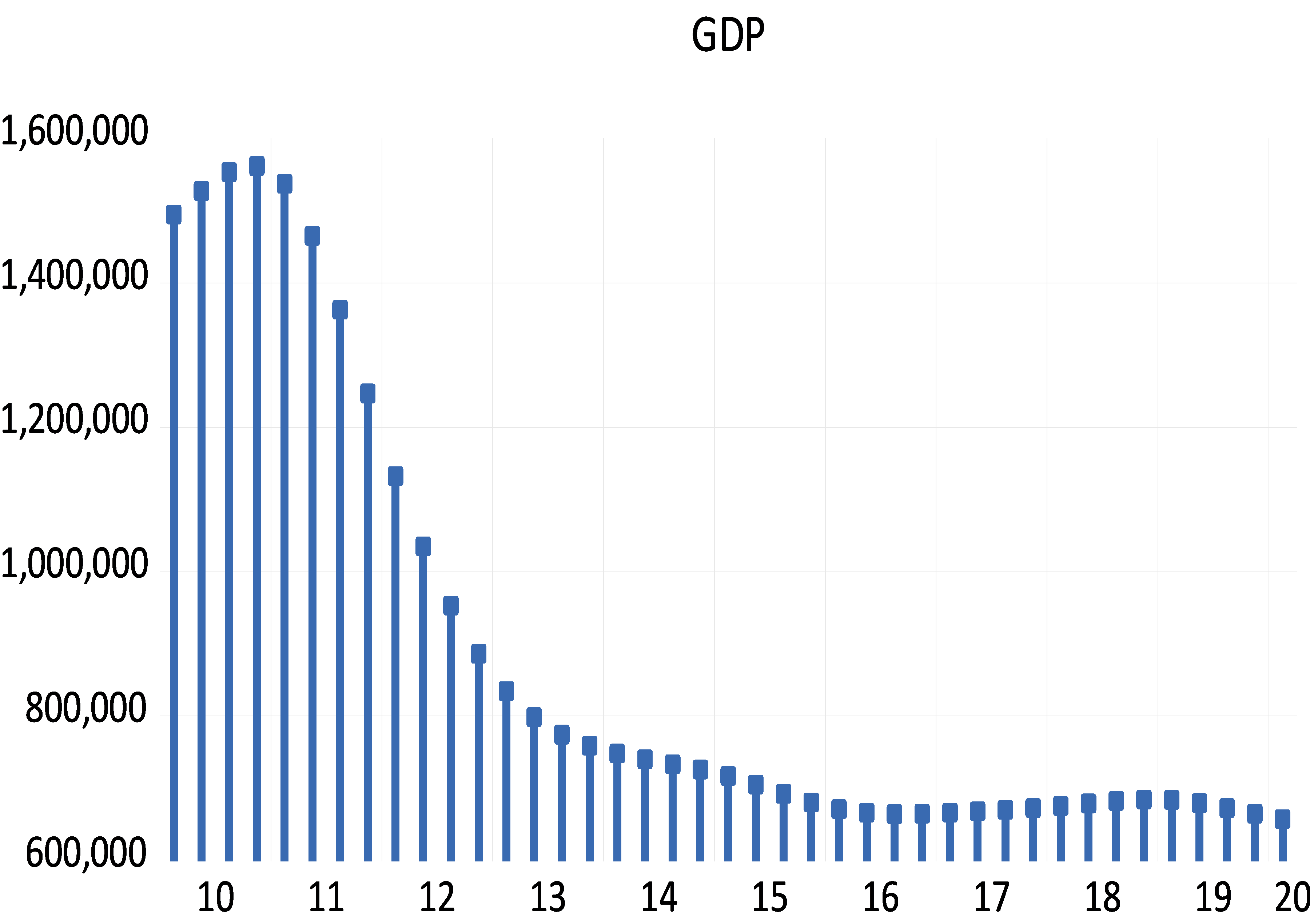

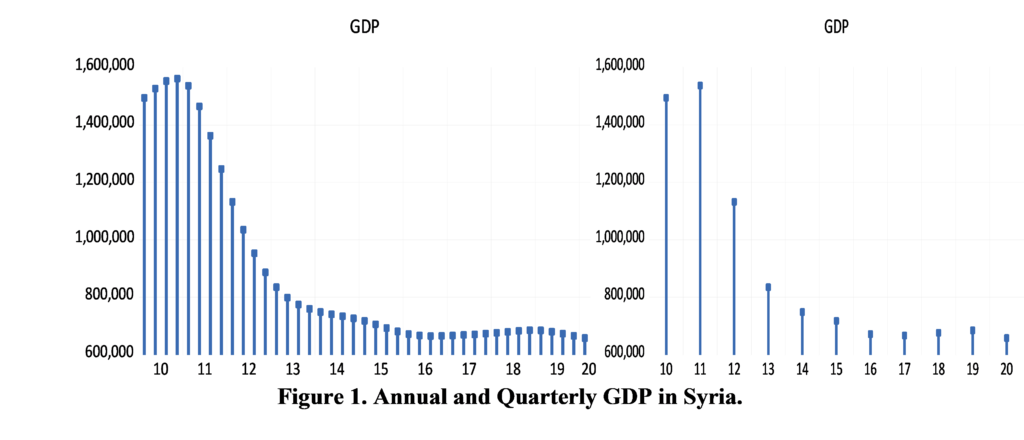

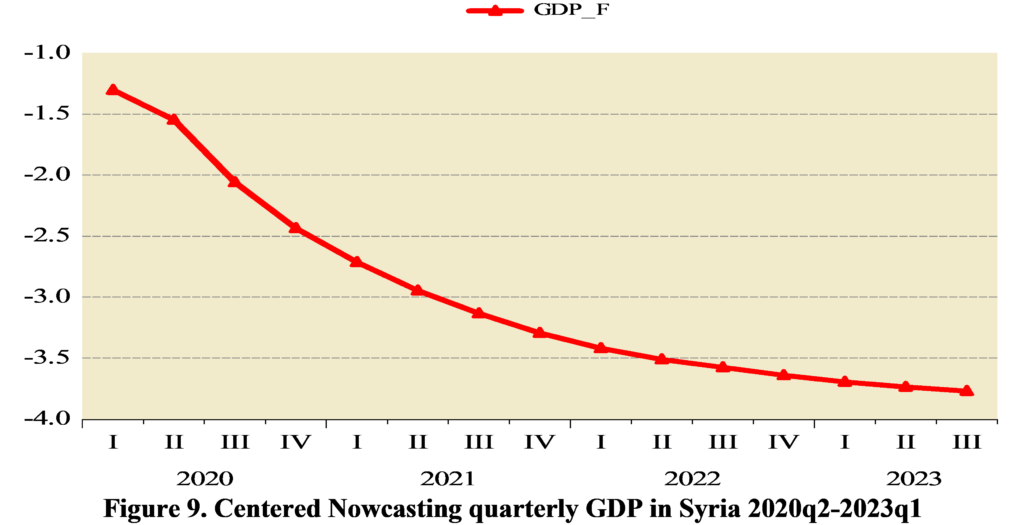

RESULTS & DISCUSSION

As mentioned, the data consists of high and low frequency variables collected from the websites of official Syrian organizations and the World Bank [41-46], summarized in Table 1, which shows basic information about data. The data of the variable GDP were collected annually and converted using the combination of Chow-Lin’s Litterman methods, (Fig 1), which shows that the volatility in annual GDP was explained by the quarter according to the hybrid method used, and gives us high reliability for the possibility of using this indicator in the model. For high-frequency data, the monthly closing price was collected from the sources listed in Table (1) and its most recent version was included in the model to provide real-time forecasts.

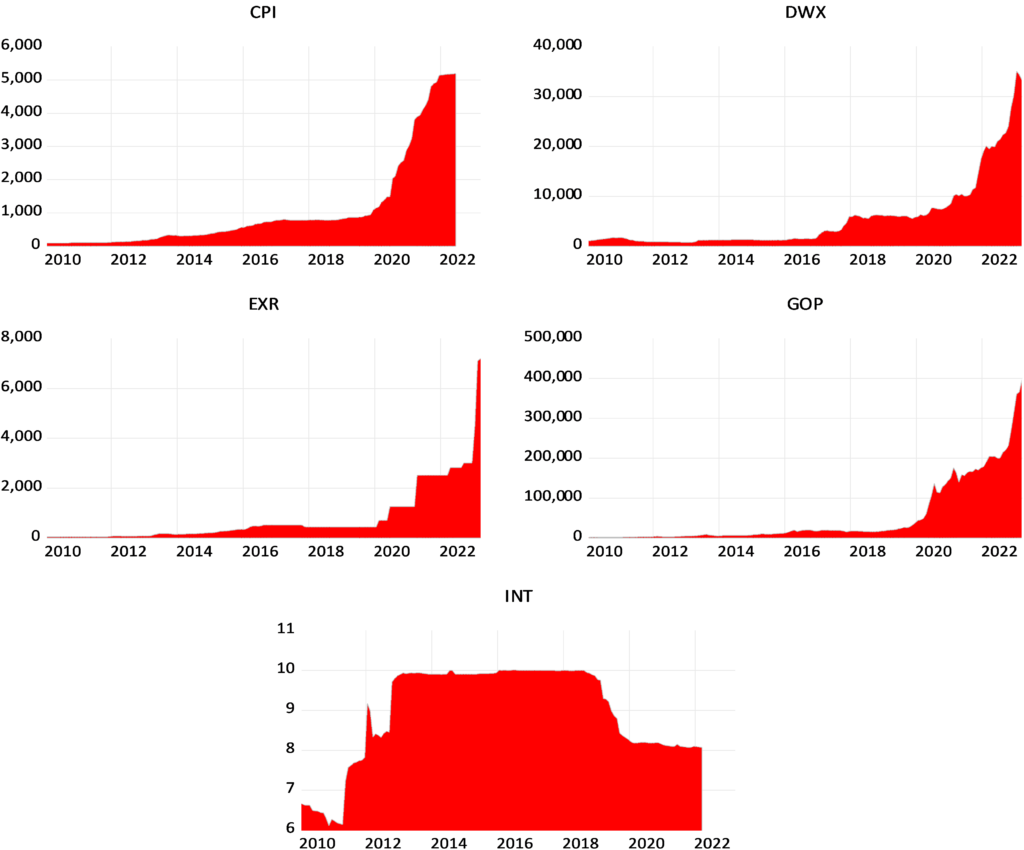

Figure (2) shows the evolution of these variables. We presented in Figure (2), the data in its raw form has a general stochastic trend and differs in its units of measurement. To unify the characteristics of this data, growth rates were used instead of prices in this case, or called log, because of their statistical properties. These features are called stylized facts; first, there is no normal distribution. In most cases, the distribution deviates to the left and has a high kurtosis. It has a high peak and heavy tails [47]. Second, it has the property of stationary and there is almost no correlation between the different observations [48]. The log of this series is calculated.

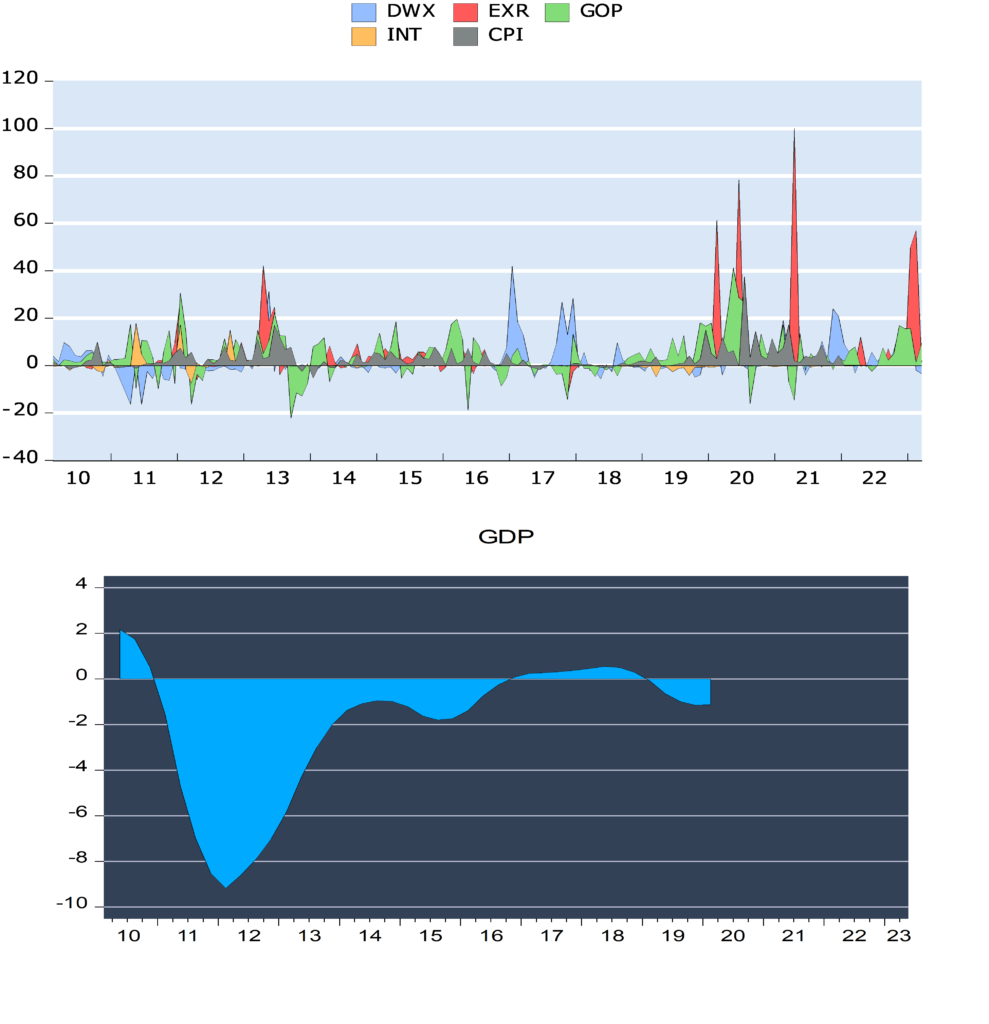

Figure 2. Evolution of high frequency study variables

Figure (3) shows the magnitude growth of the macroeconomic and financial variables in Syria during the indicated period. We note that the data is characterized by the lack of a general trend and volatility around a constant. We found that the fluctuations change over time and follow the characteristic of stochastic volatility that decreases, increases and then decreases. We found that the most volatile variable is the exchange rate (EXR) and the period between 2019 and 2020 is the one when the variables fluctuated the most due to uncertainty and US economic sanctions. We also noted that the periods of high volatility are offset by negative growth in Syria’s GDP. Using the following Table (2), we show the most important descriptive statistics for the study variables.

*** denotes the significance of the statistical value at 1%. ** at 5%. * at 10%.

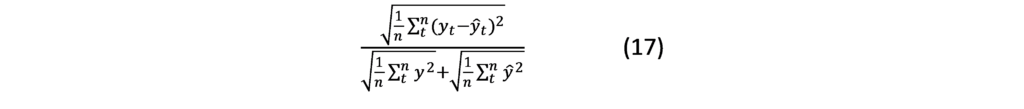

Table (2) shows that the probability value of the normal distribution test statistic is significant at 1%, and we conclude that the data on the growth rates of the Syrian economy is not distributed according to the normal distribution, and both the mean and the standard deviation were not useful for the prediction in this case since they have become a breakdown. We also note from Table (2) the positive value of the skewness coefficient for all variables, and therefore the growth rates of economic variables are affected by shocks in a way that leads to an increase in the same direction, except for the economic growth rate, in which the shocks are negative and the distribution is skewed to the left. We also found that the value of the kurtosis coefficient is high (greater than 3 for all variables), indicating a tapered leptokurtic-type peak. Additionally, we noted that the largest difference between the maximum and minimum value of the variable is the exchange rate, which indicates the high volatility due to the devaluation of the currency with the high state of uncertainty after the start of the war in Syria. Also, one of the key characteristics of growth rates is that they are stable (i.e. they do not contain a unit root). Since structural changes affect expectations, as we have seen in Figure (1), there is a shift in the path of the variable due to political and economic events. We hence used the breakpoint unit root test proposed by Perron et al [49-50], where we assume that the structural change follows the course of innovation events and we test the largest structural breakpoint for each variable and get the following results:

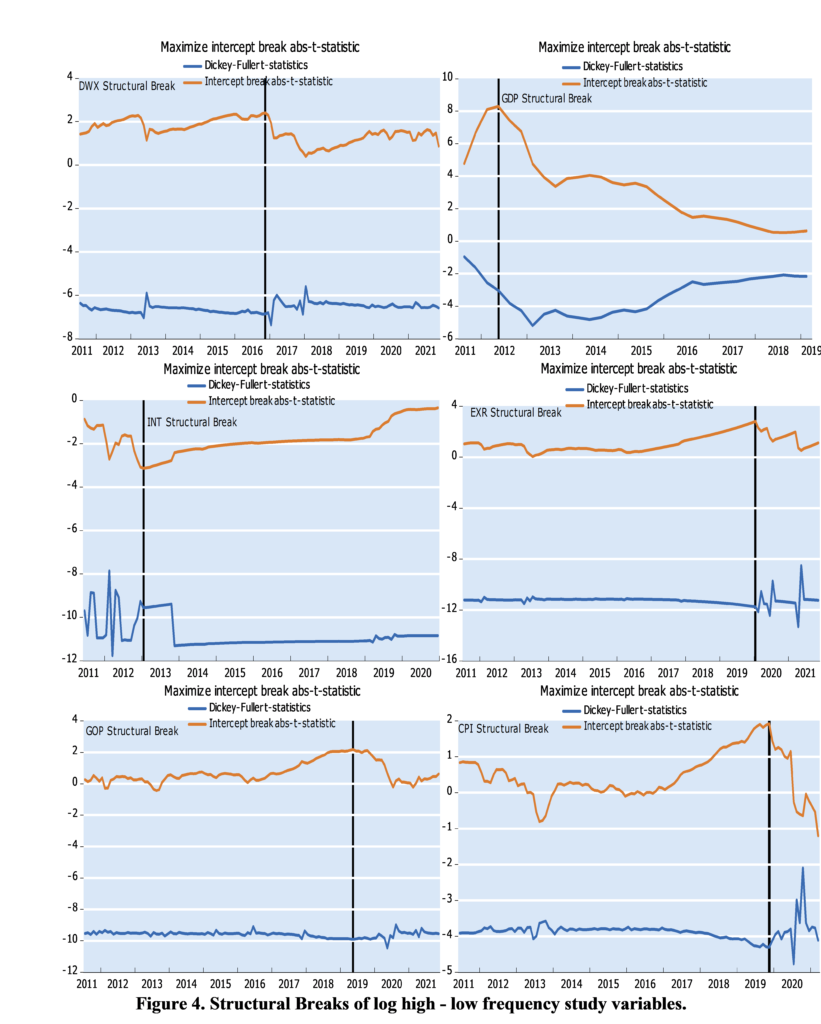

![]()

Where is break structural coefficients, is dummy variable indicated on structural change, : intercept, : lag degree for AR model. Figure (4) shows the structural break estimate for the study variables. Structural break refers to a change in the behavior of a variable over time, shifting relationships between variables. Figure (4) also demonstrates that all macroeconomic variables have suffered from a structural break, but in different forms and at different times, although they show the impact of the same event, namely the war in Syria and the resulting economic blockade by Arab and Western countries, as all structural breaks that have occurred after 2011. We found that in terms of the rate of economic growth, it has been quickly influenced by many components and patterns. For EXR, CPI, GOP, the point of structural change came after 2019, the imposition of the Caesar Act and the Corona Pandemic in early 2020, which resulted in significant increases in these variables. We noted that the structural break in the Damascus Stock Exchange Index has occurred in late 2016 as the security situation in Syria improved, resulting in restored investor confidence and realizing returns and gains for the market.

The step involves imposing the initial information on the structure of the model according to the properties of the data. Based on the results of the exploratory analysis, the prior Minnesota distributions were considered a baseline, and the main parameter is included in the hierarchical modeling:

Rho H = 0.2 is high frequency AR(1), Rho L = 0 is low frequency AR(1), Lambda = 5 is overall tightness, Upsilon HL = 0.5 is high-low frequency scale, Upsilon LH = 0.5 is low-high frequency scale, Kappa = 1 is exogenous tightness. C1 = 1 is residual covariance scale. The number of observations in the frequency conversion specifies the number of high frequency observations to use for each low frequency period. When dealing with monthly and quarterly data, we can specify that only two months from each quarter should be used. Last observations indicate that the last set of high-frequency observations from each low-frequency period should be used. Initial covariance gives the initial estimate of the residual covariance matrix used to formulate the prior covariance matrix from an identity matrix, specifying the number of Gibbs sampler draws, the percentage of draws to discard as burn-in, and the random number seed. The sample is divided into 90% training (in–of –sample) and 10% testing data (out-of–sample).

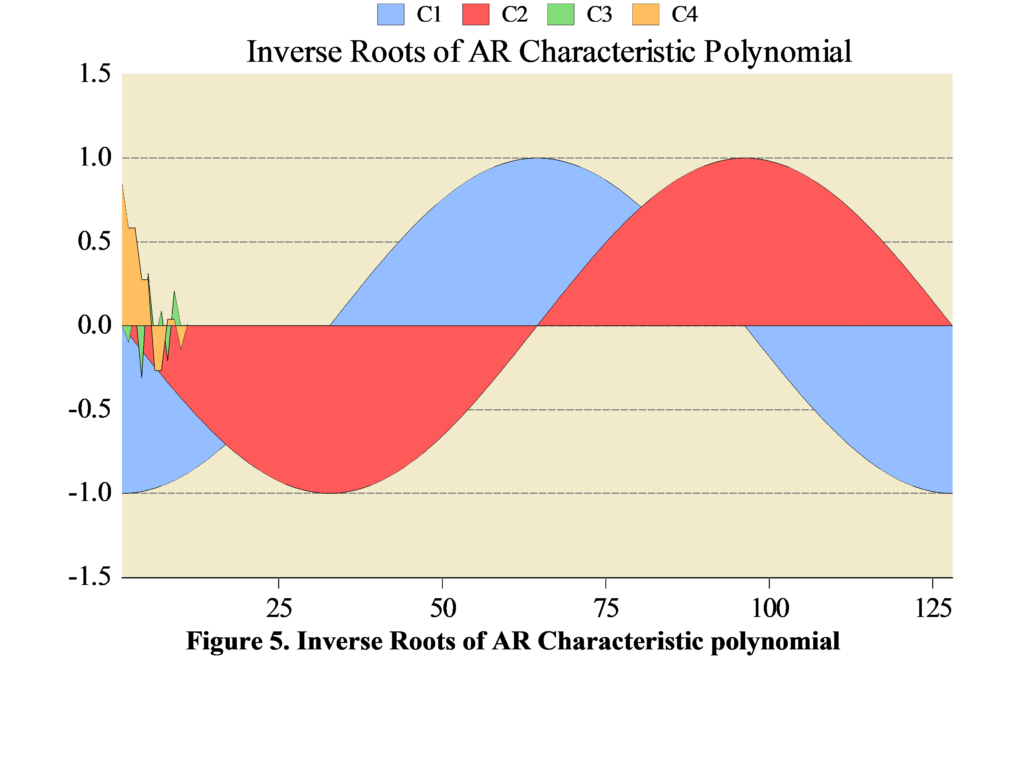

Table (3) provides us with the results of estimating the model to predict quarterly GDP in Syria. The results show the basic information to estimate the prior and posterior parameters, and the last section shows the statistics of the models such as the coefficient of determination and the F-statistic. We note that every two months were determined from a monthly variable to forecast each quarter of GDP in the BMFVAR model. Although there is no explanation due to the imposition of constraints, the model shows good prediction results with a standard error of less than 1 for each parameter and a high coefficient of determination of the GDP prediction equation explaining 93.6% of the variance in GDP.

Figure (5) also shows us the reliability of the prediction results. It is clear that the roots of the estimation of the parameters follow the inverse AR polynomial process. The inverted AR roots have modules very close to one which is typical of many macro time series models.

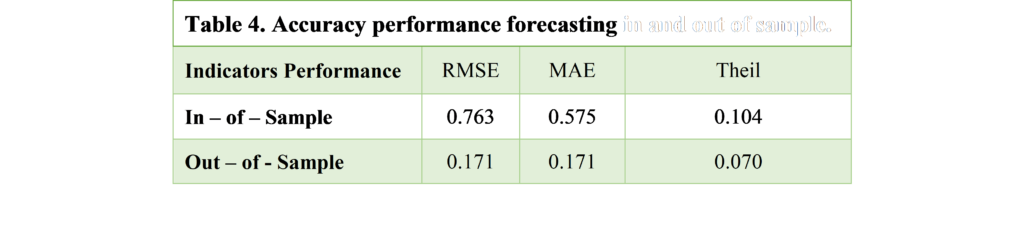

Table (4) shows the evolution of GDP Forecasting in Syria in and out the sample based on a number of indicators. When the value of these indicators is close to 0, the estimated values are close to the actual values, which is shown by Table 4, since the values of these indicators are all less than 1. The out-of-sample predicted values show a better performance of the model, and hence it can be adopted to track changes in quarterly GDP over time. Up-to-date with current versions.

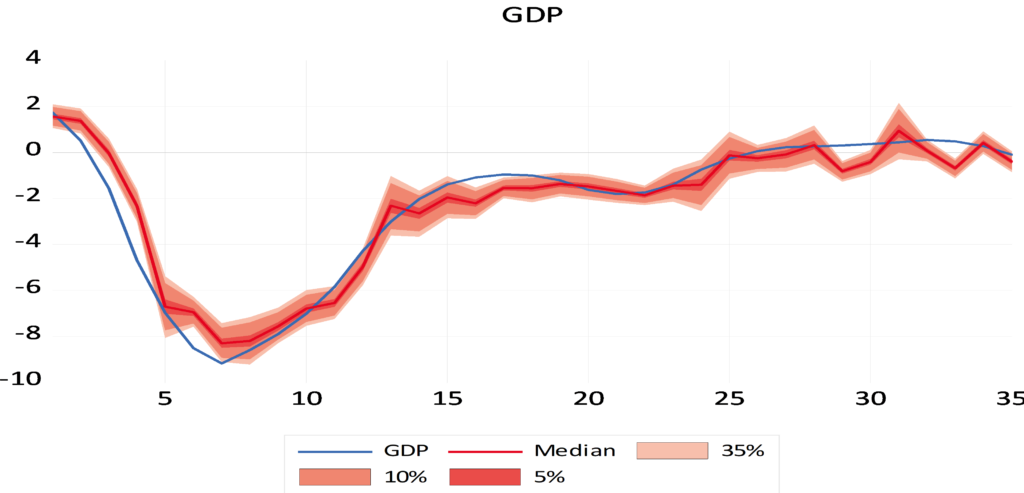

Through the data visualization technique, Figure (6) shows us the closeness of the expected values of quarterly GDP in Syria in of sample, which leads to the exclusion of the presence of an undue problem in the estimate (overfitting – underfitting). The median is used in the prediction because it is immune to the values of structural breaks and the data are not distributed according to the normal distribution. The out-of-sample forecast results (Fig 7) also indicate negative rates of quarterly GDP growth in Syria with the negative impact of internal and external shocks on the Syrian economy with the accumulation of the impact of sanctions, the lack of long-term production plans and the ineffectiveness of internal monetary policy tools, as the latest forecasts for GDP growth this quarter are (-3.69%).

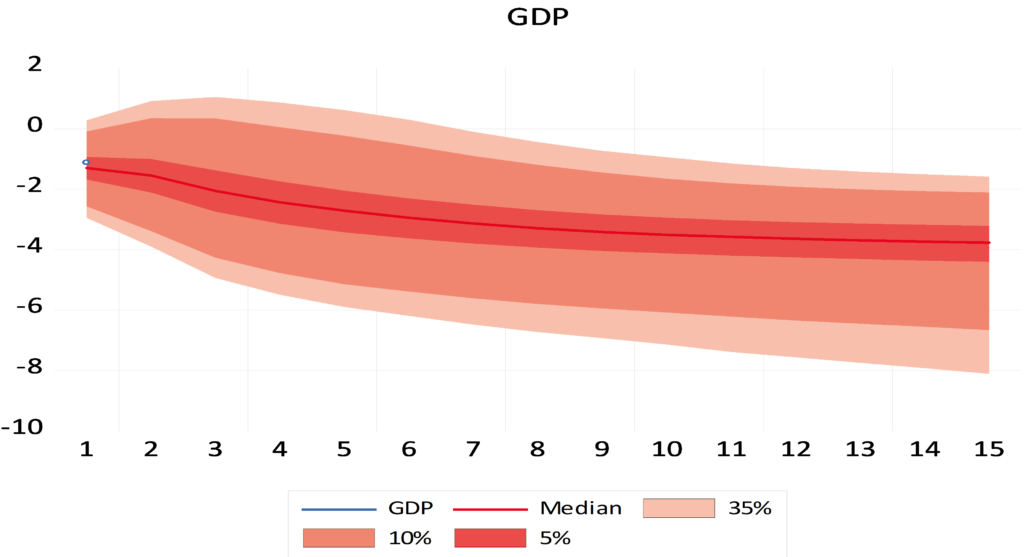

The uncertainty at each point in time is included in the Syrian GDP projections, thereby achieving two objectives: incorporating the range of GDP change at each point in time and knowing the amount of error in the forecasts. We found that uncertainty increases as the forecast period lengthens (Figures 8-10).

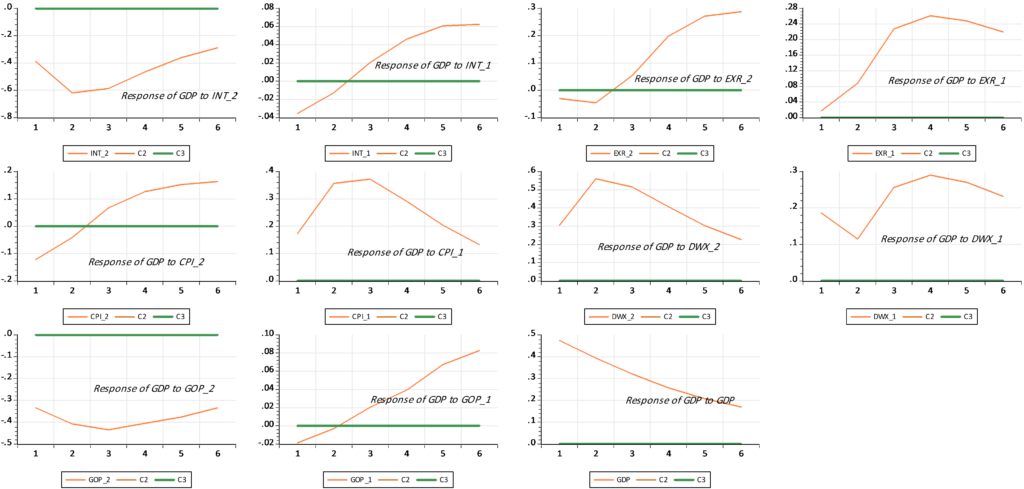

The model also provides us with important results through scenario analysis. Figure 11 shows that the quarterly GDP in Syria is affected by the shocks of high-frequency variables, since this Figure shows that the shocks have negative impacts. This recommends a better activation of the instruments of The Central Bank and those responsible for monetary policy in Syria. These results are considered important tools for them to know and evaluate the effectiveness of their tools.

Figure 6. Forecasting quarterly GDP in Syria in of sample with 35%, 10%, 5% distribution quantities.

Figure 7. Forecasting quarterly GDP in Syria out of sample with 35%, 10%, 5% distribution quantities.

Figure 8. Uncertainty for forecasting quarterly GDP in Syria in-of –sample

Figure 10. Uncertainty for forecasting quarterly GDP in Syria out-of –sample

Figure 11. Shocks of high-frequency variables in the quarterly GDP of Syria

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

This paper showed that BMFVAR could be successfully used to handle Parsimony Environment Data, i.e., a small set of macroeconomic time series with different frequencies, staggered release dates, and various other irregularities – for real-time nowcasting. BMFVAR are more tractable and have several other advantages compared to competing nowcasting methods, most notably Dynamic Factor Models. For example, they have general structures and do not assume that shocks affect all variables in the model at the same time. They require less modeling choices (e.g., related to the number of lags, the block-structure, etc.), and they do not require data to be made stationary. The research main finding was presenting three strategies for dealing with mixed-frequency in the context of VAR; First, a model – labelled “Chow-Lin’s Litterman Method” – in which the low-frequency variable (Gross Domestic Product) is converted from annual to quarterly with the aim of reducing the forecast gap and tracking the changes in the GDP in Syria in more real-time and reducing the gap of high-frequency data that we want to predict usage. Second, the research adopts a methodology known as “blocking”, which allows to treat higher frequency data as multiple lower-frequency variables. Third, the research uses the estimates of a standard low-frequency VAR to update a higher-frequency model. Our report refers to this latter approach as “Polynomial-Root BVAR”. Based on a sample of real-time data from the beginning of 2010 to the end of the first quarter of 2023, the research shows how these models will have nowcasted Syria GDP growth. Our results suggests that these models have a good nowcasting performance. Finally, the research shows that mixed-frequency BVARs are also powerful tools for policy analysis, and can be used to evaluate the dynamic impact of shocks and construct scenarios. This increases the attractiveness of using them as tools to track economic activity for both the Central Bank of Syria and the Central Bureau of Statistics.

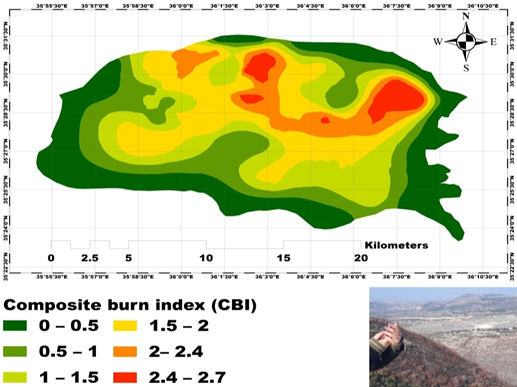

INTRODUCTION