INTRODUCTION

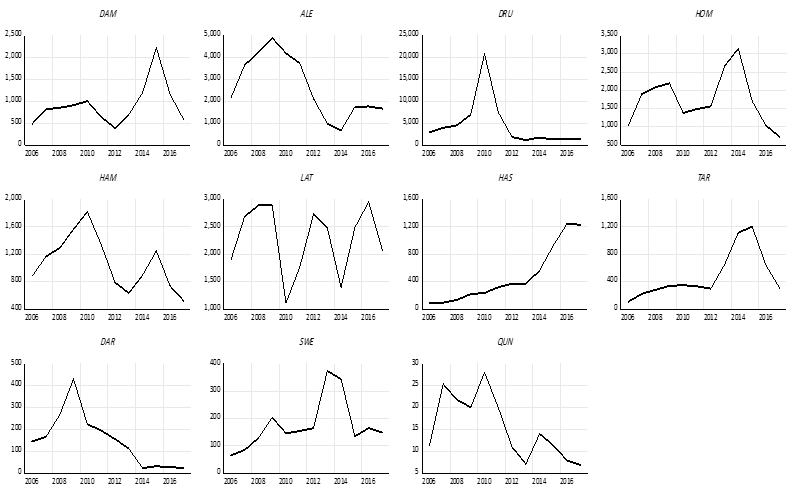

Pollution is a major problem that modern societies suffer from. The presence of pollutants in water resources, especially fresh water, makes it a serious and defining problem for growth and life [1].Pollution issues are constantly exacerbated in Coastal areas because of the increasing of population density and human activities that pollute the environment and natural resources, including water sources and groundwater which represents the reserve stock of water used in various fields [2] Environmental pollution affects all elements of the living environment such as plants, animals and humans, as well as the composition of non-living nature elements such as air, water and land. This problem has exacerbated in recent decades and become a grave danger threatening all living organisms because of industrial development, technological progress, and the development of the human standard of living accompanying with the increasing in consumption and the growing dumping of waste in the environment [3, 4] Solid waste is considered one of the major environmental problems in urban areas, due to its direct impact on the quality of human life, the appearance of civilization, and the consequent serious negative impact on sustainable development [5]. Solid waste resulting from various human activities (production and consumption) has become a major threat to the environment and people because of the increasing quantities generated daily which exceed the ability of the environment to decompose and convert them into useful or harmless materials [4]. The increasing production of raw materials and their consumption contributed to the depletion of natural resources and caused continuous damage to the environment [3]. Every year, the production of raw materials destroys millions of hectares of land and trees and produces billions of tons of solid waste. It pollutes water and air [6], in addition to the pollution resulting from the production and use of energy needed to extract and manufacture materials [7]. Surface water bodies have been used for a long time, and are still used today, as places for discharging various human waste, which exacerbated the problem of fresh water pollution in rivers, lakes and water reservoirs due to a change in its physical, chemical or biological properties. In addition to the pollution caused by these wastes to groundwater when the leachate reaches it [8]. The presence of indiscriminate dumping near water resources (ground or surface) contributes to their pollution and the pollution of the environment in all its aspects, especially groundwater, which represents the reserve stock of water used in various fields affecting growth and life, [9 ,10]. In wet weather, the movement of chemical and biological pollutants of solid waste materials is active, their concentration increases at the bottom of the landfill [11]. Most of leachate coming out of the landfills increases during periods of precipitation. solid waste forms severe pollution sources due to the abundance and diversity of chemical elements emerging from them[12]. Problems with health and environment increase with the appearance of some heavy metals in the groundwater, as specialized references confirm that their presence (no matter how small) is linked to solid waste, as it is one of the most dangerous and toxic chemical pollutants for living organisms [13, 10, 14], and is characterized by its long-term persistence in the aqueous medium, which ranges from several months to several years [14, 15]. The development which Syria witnessed in recent decades has been accompanied by the emergence and exacerbation of environmental pollution problems, as the surface and groundwater in the country suffer from the accelerating rate of bacterial and chemical contamination with industrial, domestic, and fertilizer waste [5]. It has been shown that the pollution, and the amount of waste in general, has increased with the increasing in the population in the countryside and cities, because of the weakness of the treatment plants. [16]. One study also showed an increasing in bacterial population in the water of wells used to irrigate some vegetables near the waste dumping site in the Al-Bassa area in Lattakia during winter [17]. In the same context, the study of the environmental impact of the Al-Bassa landfill [18] concluded that some indicators of contamination of groundwater wells in the Al-Bassa area increased, and it was noted that the rates of BOD and NO3 increased above the permissible levels for drinking water. Another study showed bacterial and physiochemical contamination of the waters of the Al-Kabir Al-Shamali River in the Al-Jindiriya area [19]. The importance of this research lies in evaluating the quality of water in the wells located in the vicinity of Wadi Al-Hada Center, in addition to the clear environmental effects of waste leaching on some groundwater wells located in the vicinity of it, especially after the appearance of turbidity in two wells located in Beit Ismael and Minya Yahmour villages. The research aims to monitoring and evaluating the quality of groundwater within ten wells located in five villages adjacent to the center of Wadi Al-Hada by determining some physical and chemical characteristics of groundwater in two wells from each village for a period of four months (until the results of the analysis became identical to the Syrian standard specifications) and determining measures to reduce the impact of major water pollutants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study site and sampling sites:

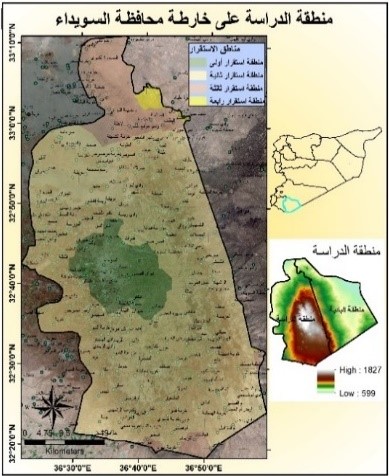

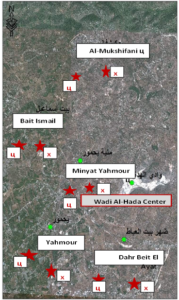

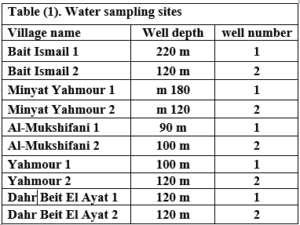

This research was conducted in the area surrounding the Wadi Al-Hada Center for Solid Waste Treatment, located in the village of Al-Fatasiyah, 13 km southeast of Tartous, and at an altitude of about 180 meters above sea level. The area of the center’s land is 100 dunums. several sites next to the center are used for dumping waste resulting from the center. The center is surrounded by a group of small villages and residential communities working in agriculture (these are the villages of Yahmour, Al Zarqat, Minyat Yammour, Karm Bayram, Beit Ismail, and others…) The irrigation of crops in these villages depends on groundwater. The idea of this research came from the appearance of detectable pollution in two wells located in Minyet Yahmour and Beit Ismail, due to exposure to waste leaching. The research was divided into two stages In the first stage, a survey was conducted by distributing questionnaires to local population. This questionnaire covered 50 families, and included questions to explore their opinions about the center, their health conditions, diseases suffered by family members, and the repercussions of water pollution on them due to the old dump and treatment center in Wadi al-Hada, and the availability of a sewage network in the area. In the second stage, the impact of Wadi Al-Hada center on some wells in five villages adjacent to it was studied as shown in Figure 1. Groundwater samples were taken from 10 artesian wells (Table 1) distributed in the region, so that they represent the various conditions of the site in terms of human activity and land use, and analyzes were conducted.

Several field visits were made to the study site, and water samples were taken from these wells six times, at an interval of ten to twenty days. The sampling was stopped when the results became in conformity with the Syrian standard specifications starting from 7/27/2021 until 10/12/2021. Sample collection and analysis: Samples were collected in 1-liter polyethylene containers to determine the COD index and measure some electrolytes. The containers were washed well with distilled water and study site water three times before being filled; other samples were collected in 500 ml glass containers to determine the number of faecal bacillus FC. The containers were sterilized in an oven at a temperature of 250ºC for two hours Water analyses were conducted in the laboratories of the Directorate of Water Resources in Tartous Governorate, as follow:

Several field visits were made to the study site, and water samples were taken from these wells six times, at an interval of ten to twenty days. The sampling was stopped when the results became in conformity with the Syrian standard specifications starting from 7/27/2021 until 10/12/2021. Sample collection and analysis: Samples were collected in 1-liter polyethylene containers to determine the COD index and measure some electrolytes. The containers were washed well with distilled water and study site water three times before being filled; other samples were collected in 500 ml glass containers to determine the number of faecal bacillus FC. The containers were sterilized in an oven at a temperature of 250ºC for two hours Water analyses were conducted in the laboratories of the Directorate of Water Resources in Tartous Governorate, as follow:

Working methods:

Physical, chemical and bacteriological analysis were carried out in the laboratories of the Directorate of Water Resources in Tartous, according to the following: Some physical indicators (pH, turbidity, and electrical conductivity) were measured at the study site using newly calibrated field devices as follows:

- The degree of pH was measured using a field pH device from HACH, model Sension 1. As for turbidity (Turb), a turbidity device from HACH, model 2100P, was used, and a conductivity device from WTW, model Cond 720, was used to measure electrical conductivity (Cond).

- The electrolytes (chlorine – sulfate – nitrite – nitrate – phosphate – ammonia) were measured using an IC device

- COD – (Chemical Oxygen Demand): The COD was determined using the open tube method, where the samples were digested at 150 degrees Celsius for two hours in a COD sample digester from VELP Scientifica, model ECO, in the presence of mercury sulfate, silver sulfate, sulfuric acid, and potassium dichromate. Then, the samples were calibrated using ferrous ammonium sulphate.

FC – (fecal coliform count): FC was determined using the filtration method on 0.45-micron bacterial membranes and incubated with MFC agar culture medium at 37.5°C for 24 hours using the following equipment: Bacterial isolation chamber from Lab Tech, buchner funnel for filtering bacterial samples, a bacterial incubator from Memmert, a sterilization oven from Memmert, and an autoclave from SELECTA, model AUTESTER ST

RESULTS

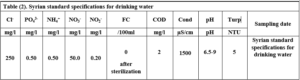

At the beginning of the research, the wells in Minyat Yahmour and Beit Ismael were polluted, due to the exposure of the aquifer to pollution by the waste leaching collected next to the center, but when the leachate was collected, the results returned to the permissible limits according to the Syrian standard specifications shown in “Table2”.

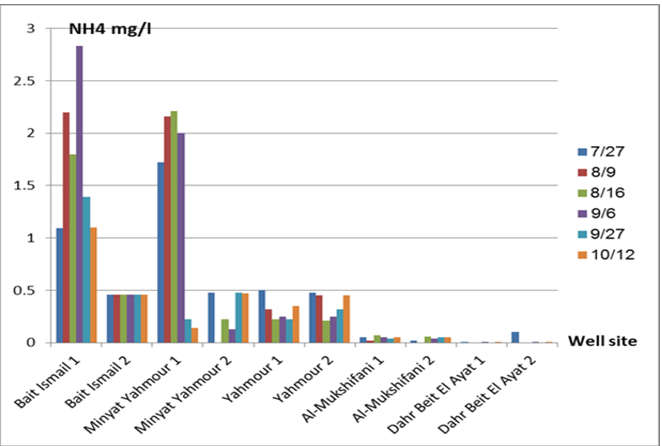

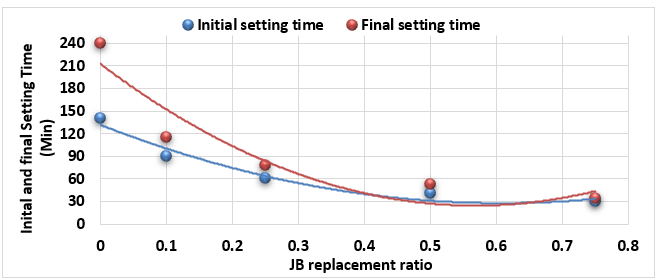

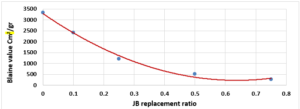

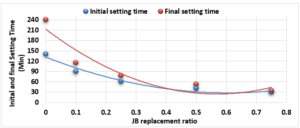

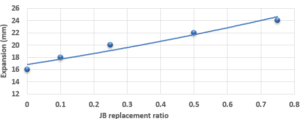

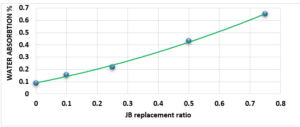

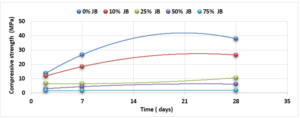

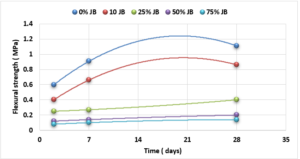

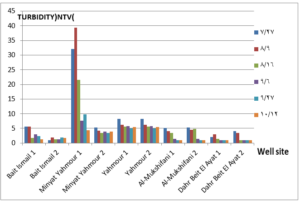

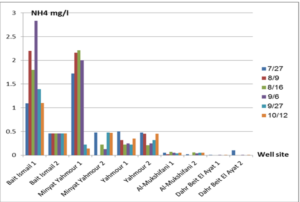

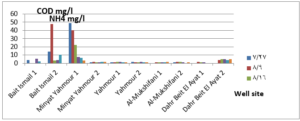

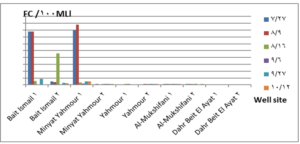

The pH values were moderate values tending to alkalinity, and were within the permissible limits according to the Syrian standard specifications and so was the electrical conductivity (Cond) which did not exceed 813 μM/cm in the wells. Whereas turbidity values were high in most of the wells in the first samples during July and August, especially in (well 2) Minyat Yahmour, where it reached (39ntu, 32ntu), and in (well 1) Yahmour (8ntu.2ntu) “Fig 2”. We also noted that the percentage of ammonia was above the permissible limits according to the Syrian standard specifications. “Fig 3”. COD values in all measurement locations exceeded the permissible limits according to the Syrian standard specifications (which is 2 mg/L) in the first samples, ( in July and August), “Fig 4”, and also the results of the bacteriological analysis showed high general count and a high number of coliform bacilli in the two wells located in Beit Ismail and well 2 located in Minyet Yahmour, “Fig 5” Finally, positive and negative electrolytes, It was noted that the values of the ions NO2-، NO3- ، PO43-، Cl-، SO42-did not exceed the permissible limits according to the Syrian standard specifications in the ten wells. Population survey results: The results of the questionnaire showed the occurrence of disease cases as a result of the use of contaminated well water.

DISCUSSION

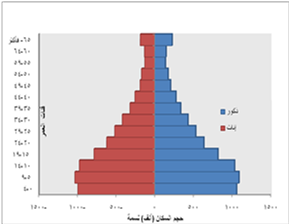

We will graphically review only the indicators that do not conform to the Syrian standard specifications and analyze their changes spatially and temporally. The pH values were within the permissible limits according to the Syrian standard specifications. There was no significant change in them according to the change in the sampling date or the location of the well. As for turbidity, we noticed high turbidity values in most of the wells in the first samples, and we can attribute this to the leaching of pollutants from the landfill into the effluent that heads from Wadi al-Hada center towards Minyat Yahmour and Beit Ismail. Then, the values of turbidity decreased until it became within the permissible limits according to the Syrian standard specifications in November. This is because the problem was solved in the area and the leachate was collected in the rainwater collection basin and This is consistent with studies confirming the impact of landfill leachate on groundwater [20, 21] The measurements also indicated that the electrical conductivity values of well water and surface water were within the permissible limits according to the Syrian standard specifications (1500 µm/cm), but the ammonium ions in the water influenced by human activity as the nitrogen was presented in polluted water (urine and uric acid). The production of ammonium ion during the ammonification process indicates the recent existence of contamination with organic matter and the progress of the self-purification process that carried out by microorganisms in aquatic media. [22].COD values: It is noted from “Fig 4” that the COD index has increased, as the highest value was recorded in well 2 located in Minyet Yahmour and the two wells located in Beit Ismail, but these values began to decline until they became within the permissible limits in the month of November, and this indicated that the aquifer was contaminated with highly concentrated organic matter that may be due to the leachate from Wadi Al-Hada. The discrepancy in the results between the wells can be explained by the difference in the slope and permeability of the soil and rocks at this location compared to the locations of other wells [4] “Fig 5” shows the bacteriological analysis that it exceeded the permissible limit (which is zero) in all wells except for the (two wells) in Dahr Beit Al-Ayat and (well 1) in Minyet Yahmour,the value (zero) was recorded which was good . The largest value was in the two wells (well l) in Beit Ismail and ( well 2) in Minyet Yahmour, during the first three months (July, August and September). This may be due to the fact that there is sewage near them. As for the rest of the wells, the number of coliform bacilli was greater than zero, but it was relatively less than these wells and this is consistent with studies confirming the impact of waste leaching on the groundwater [23, 24] Positive and negative electrolytes: It was noted that the values of the ions NO2-, NO3-, PO43-, Cl-, SO42- did not exceed the permissible limits according to the Syrian standard specifications in the ten wells during the four months. This can be explained by the fact that they were not subjected to excessive fertilization, and this was indicated by many studies [25,26,27]; However, the results showed an increase in the concentration of ammonia ions in the two wells located in Beit Ismail and Minyat Yahmur. It was also found that there is no clear relationship between the depth of the well and the values of the pollution indicators in it. This can be attributed to the fact that the studied wells were not fed by the same aquifer [28]. It is important here to point out a study on Modeling the movement and transport of pollutants in the groundwater using GMS program (a quantitative model using MODFLOW, and a qualitative model using MT3D), which was conducted at (Al-Bassa Dump) [29], and the results of the quantitative modeling of the water resources system in the Al-Bassa Dump area resulted in obtaining a map of Head Contours and flow Budgets, and the ability to display cross-sections at any point of the studied area. We also were able, through qualitative modeling, to simulate the transport of pollutants, and the leakage of leachate from Al-Bassa Dump, and predict its expected changes during different periods. Therefore, it is necessary to emphasize the importance of using modeling programs to predict the movement of pollutants in the Wadi Al-Hada center area. Population survey results: The results of the questionnaire showed the occurrence of disease cases as a result of the use of contaminated well water, the most important of which were acute intestinal diarrhea and gastrointestinal infections. 30% of the surveyed people indicated that they were exposed to diseases because of the landfill or as a result of their use of groundwater wells, and most of them stopped using this water for drinking and only used it to irrigate crops. The results also showed that 80% of the population are farmers and have lived in the area for more than 50 years, and 25% of them depend on technical drilling.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

We can conclude from this study the following main points:

- The water wells in the villages of Minyat Yahmour and Beit Ismael were exposed to significant microbial contamination. High COD values were also recorded. This is an evidence of exposure to contamination by landfill leachate and sewage leakage

- The groundwater at the site was subjected to temporary pollution that made it unfit for drinking, but after four months it became fit for drinking and within the limits of the Syrian standard specifications

- The use of contaminated well water has led to disease cases, the most important of which are acute intestinal diarrhea and gastrointestinal infection

RECOMMENDATIONS

To avoid the health and environmental harms of the waste and sewage water, we recommend the following:

- Emphasis on the need to construct rain drains and trenches throughout the center, and as for the landfill, emphasis must be placed on covering up and isolating both base and sides to ensure that there is no leakage into the nearby groundwater.

- Studying the characteristics of the leachate resulting from the landfill in the future, and evaluating its impact on the surrounding environment.

- -monitoring groundwater in the surrounding area and checking the change in the concentration of pollutants in them

- Modeling the movement and transport of pollutants in the groundwater using Modflow and MT3D

Use a modeling program to predict pollutants by constructing a mathematical model using GMS program (a quantitative model using MODFLOW, and a qualitative model using MT3D).